Alexander Gardner: The Last of the Native Americans

After the Louisiana Purchase, the new maps designated the vast stretch of land west of the 100th meridian as “the Great American Desert.” To the eighteenth century mind, this territory, dry and dusty, overrun with wild animals and populated by hundreds of native tribes, was entirely unsuitable for European habitation. Although the United States “owned” the midwest–having purchased it from France–administrations after Thomas Jefferson were content to leave thousands of square miles to the Native Americans. But times changed and with them the needs of a rapidly growing nation, now full of incoming immigrants and war scarred survivors anxious to start over–all wanting to find new lives. American policy towards the indigenous population changed from one of benign neglect to an intent to “civilize” the “savage” “barbarians,” by wiping out their culture and seizing their homelands for productive use by farmers. It is precisely at this turning point in history that the Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner arrived in the western territory of Kansas with his cameras, his glass plates, and his wagon load of equipment, ostensibly to document the “progress” of the Kansas Pacific Railroad as it progressed toward the Pacific Ocean. Fresh from the battlefields of Antietam and Gettysburg, in 1867 Gardner found himself squarely in the middle of a ruthless relocation operation, in which a large Native American population of some 100,000 people were to be moved from their ancestral lands to reservations set aside for their use by the occupying army of the United States.

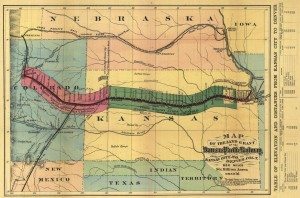

The Kansas Pacific Railroad and the Land Grants as it existed when Gardner was in Kansas (1869)

The building of the railroad was dependent upon the relocation of the Native Americans and the mindsets of the corporate developers and the military that aided them was highly hostile to the natural elements of the west, from the buffalo that supported the native population and to the natives themselves. Gardner’s collodion photographs, now understood as a unique record of two alien cultures encountering each other, whether through technology or treaty, were made in two versions for two purposes. The numerous stereographs of the building of the railroad were cheap and easy to sell to a broad public, interested in watching the progress of conquest. The Imperial or large format plates of the West were more suited for public exhibitions and were considered closer to works of art or at least as important and significant accomplishments on the part of the maker. According to John Charlton, the railroad photographs were first seen in the mundane report by the Kansas Pacific titled Surveys Across the Continent 1867-68 on the thirty -fifth and thirty-second Parallels For a Route extending the Kansas Pacific Railway to the Pacific Ocean at San Francisco and San Diego. Charlton quoted the author of the report General William Palmer as connecting the building of the railroad to the demise of the Native Americans: “Because the railroad is the only reasonable plan that has been presented for the final settlement of the Indian question, which apart from the coast, is a problem of great concern for the nation–affecting the honor and conscience, as well as its growth..”

It is unclear if Gardner understood the dual nature of the railroad project, which was to exterminate the Native American, but it is possible to speculate that he may have indeed been cognizant of the social meaning and the cultural consequences of the railroad upon the tribes of the Great Plains. Railroad officials, government bureaucrats, Indian Agents, the military were all in agreement that the Native American had to be wiped off the face of the emerging map, one way or the other and this common assumption, as genocidal as it was, was common knowledge, spoken of among the public as freely as in Palmer’s report. It is hard to believe that the photographer could have not known of the official discourse that was growing against the Native Americans. For whatever reasons, Gardner, to an extent that was unusual at his time, took a large number of photographs of Native Americans on his road to the Pacific Ocean, possibly as a journey of penance, an homage to those who were to be extinguished.

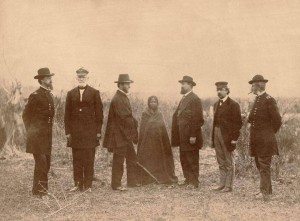

Alexander Gardner. Treaty at Fort Laramie (1868)

Therefore, Gardner’s photographs of the Native Americans raise powerful questions: what were his intentions? Was he acting as a proto-anthopologist? a tourist? a white man recording a “vanishing” species? A Lowlander recalling the British conquest of Scotland? We know that Gardner’s background was one built on a desire to create a better society. As a founding member of the Clydesdale Joint Stock Agricultural & Commercial Company, he had raised money to start a utopian cooperative community modeled on New Harmony founded in Indiana by fellow Scotsman Robert Owen. Full of hope, Owen had stated, “I left this country in 1824 to go to the United States to sow the seeds in that new fertile soil – new for material and mental growth – the cradle of the future liberty of the human race.” Like New Harmony, Gardner’s dream community of Clydesdale ultimately failed. We also know that while in Scotland, Gardner actually owned a socially conscious newspaper, the Glasgow Sentinel, which advocated rights for working class people.

Oddly little is written of this early career of advocacy and the histories of Gardner usually begin with his tenure with Matthew Brady in Washington, D. C. There is less interest in Gardner’s Western images from the post-war period, and his volume Across the Continent on the Kansas Pacific Railroad in 1867-68 is considered today to be “rare,” as is his Scenes in the Indian Country published in 1868. Thanks to his acquaintance with General William Sherman, Gardner was asked to photograph the gathering of tribes from the plains at Fort Laramie, Wyoming for a so-called Indian “Peace Commission” which would consign the Native America tribe, the Sioux to restricted reservations in the Black Hills in exchange for their vast lands. This 1868 treaty sent the Sioux to lands considered sacred to the people, but the sacredness of these lands would not be respected, and in a twist of fate, one of Gardner’s photographic subjects, in 1874 General George Armstrong Custer, would break the Treaty of Fort Laramie, invade the territory, and lead the Seventh Calvary to a defeat at the hands of the outraged tribe. Ultimately, the Sioux lost. They were forced to relinquish most of their twenty five million acres of land promised them to the rapacious settlers, land they are still trying to recover.

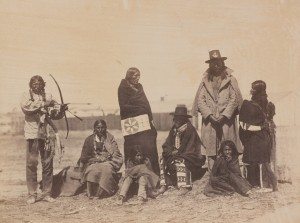

But the work by Gardner at Fort Laramie was a counterpoint to an earlier body work, commissioned by William Henry Blackmore. Blackmore was an odd character. An Englishman who hunted buffalo along the Kansas Pacific line, he was a speculator on lands and railroads of the American West and became very wealthy. Fascinated by Native Americans, Blackmore fancied himself as a friend to various chiefs and asked Gardner to photograph the delegation of Native Americans who arrived in Washington to sign a treaty in 1867. There is a later book, published in 1872, containing thirty-one images by Gardner of Photographs of Red Cloud & his Braves, including an image of Blackmore shaking hands with the famous chief Red Cloud. In 1878, Blackmore shot himself, ending his life and his financial ventures into the American West. In a book published posthumously after his death, The Hunting Grounds of the Great West, he correctly predicted the extinction of the Native American way of life. Gardner, as a recurring character in a drama, emerges from these accounts as a photographer who drifts in and out of a very troubled decade of American history as a kind of Zelig, touching all the historic markers, “being there” at all the troubled intersections where one way of life comes to an end and another comes into troubled being.

Alexander Gardner. Red Cloud, May 1872, at Washington D.C.

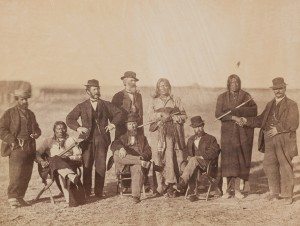

Writing in Collector Daily, Richard D. Woodward termed Gardner as “fervent” abolitionist, but he photographed Native Americans as they presented themselves, without drama or romanticism. Although Gardner must have been aware of the white animosity towards the indigenous peoples, the photographer was not to know that the tribes were signing documents that would guarantee their own agonizing demise and forced assimilation and cultural genocide. The value of Gardner’s body of photographic work lies in the lack of commentary, allowing viewers to interject their own meanings and to impose their immediate historical horizons upon the images. Gardner positioned the Native Americans and their white conquerers together, posed in the last years before a terrible decade of wars broke out, and what is demonstrated is a straightforward contrast between two completely incompatible and technologically uneven cultures. For the nineteenth century spectator, the Native Americans would have been curious relics, bloodthirsty “savages” best put to one side to make way for “civilization.” To a viewer today, the plains of Kansas suggest the last images of the last minutes of a territory that was in the process of being conquered in the name of corporate speculation. Perhaps Gardner had witnessed too closely the death and destruction during the years of a long Civil War, and perhaps, as a peaceful man, he had seen too much violence. His images of the West lack the dramatic poetics of his former assistant Timothy O’Sullivan, who was working in tandem on yet another parallel line in the West. With Gardner, there is no drama, merely a Dragnet approach to a set of facts that he presented at a careful and purposeful distance. Gardner photographed a school founded for the purpose of forcing Native American children to renounce their heritage, reflecting the thinking of the time that assimilation would be the salvation of the tribes. We cannot know if he approved or disapproved, but it is suggested that Gardner wanted the best for the future generations.

Alexander Gardner. Group with Packs His Drum, Man Afraid of His Horses, and Red Bear (1868)

In the summer of 2014, the Nelson Atkins Museum mounted an important exhibition, “Across the Indian Country: Photographs by Alexander Gardner, 1867-68,” of the two bodies of work in the west made by Alexander Gardner. As Jane L. Aspinwall, the Nelson’s associate curator of photography, pointed out, Gardner’s images are “the only photos of the Fort Laramie Treaty that exist,”

and the photographs seem to show Native Americans blank faced with shock and incomprehension, surrounded by the white officials efficiently going about their business. According to the director of the Museum, “Gardner captured images of Indian life that had rarely, if ever, been photographed. Wrapped in blankets, carrying peace pipes, many of the Indian chiefs were truly interested in peace only to be met with empty promises. These images are poignant and wistful—documenting the rich culture of a rapidly marginalized Indian population.”

The curator of the exhibition Jane L. Aspinwall added, “Gardner’s photographs emphasize his personal vision that all people, native and non-native, could live together harmoniously. The survey photographs of the Western landscape are extraordinary and provide a rare glimpse into the transformation of the American frontier, including some of the earliest images taken of the state of Kansas.”

The exhibition which closed in January of 2015 marked the photographing of the new state of Kansas, which had joined the nation in 1861. In a radio interview with Modern Art Notes, Aspinwall felt that the photographer’s railroad images, regardless of their original commercial and promotional intent, showed the desire of Alexander Gardner that the future for the new settlers and the old tribes would be one of harmony and mutual sympathy. If indeed that was his vision, which extended from Kansas to California, it was a dream destined to not come true. But Gardner has left us with a body of work of impeccable images that stress what Aspinwall called “the human” in the contested territories of early America. After this western excursion, Alexander Gardner ended his career as a photographer and went into the insurance business, with the intent of making the lives of people better. When he returned from his Western travels, Gardner tried to get the government to purchase and preserve his work on the Civil War. As with the vast Brady collection, the government was not interested, and the legacy of Alexander Gardner faded into ignominy. Unlike his mentor, Matthew Brady, he never became a “famous” photographer and when he died in 1882, his estate listed not one collodion image. He may have lived as a photographer but he died as an insurance agent, with his son Lawrence inheriting the business. But Gardner was not totally forgotten. In 2011, Michael E. Ruane wrote for The Washington Post on “Alexander Gardner: The Mysteries of the Civil War’s Photographic Giant” and of the eventual discovery of a forgotten collection of glass plate negatives by a former associate of the photographer, J. Watson Porter. Porter had worked with Gardner during the Civil War and is responsible for the accounts of his boss moving bodies for aesthetic effect. It is probable that he wanted the photographer’s work to be preserved. Although we shall probably never know how he knew where to look, Porter found a stash of negatives under the stairs of Gardner’s former home on Pennsylvania Avenue. According to Mark Katz in Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner (1999) many of Gardner’s glass negatives were used as scrap and other images were held by collectors and were therefore not public. How many of Gardner’s negatives are missing and how many of Gardner’s images have been misattributed we may never know. As Ruane noted, the fate of the stash found by Porter is unknown. It was not until 1942 that the United States government finally agreed to preserve Gardner’s pictorial history of the nation’s most terrible conflict. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.