FRENCH REVOLUTION IN ART

By the eighteenth century being part of the beaux-arts rather than being involved in “crafts” was often a matter of class. Artists tended to come from the middle class and shared the aspirations of upward social mobility typical of the bourgeoisie. Eager to please and desiring to succeed, these artists were disciplined by way of the long-standing academic training and system of rewards and punishments. For nearly a century and a half, artistic production, the education of the artists and the quality of the arts was under the auspices of the state. Each artist and every object was evaluated and all artists were trained to respond to patronage and prizes. The academic system, as restrictive as it was, was, if one played by the rules, a stable and predictable means of earning a living. But two social events would impact artists and art, especially in France, and upend the promise of guarantees. The first event was the French Revolution, which forced artists to choose between King or country, aristocracy or citizens, and, which, during the Terror, eliminated the traditional patrons, the Church and the aristocrats. The second event was a long, ongoing process: the rise of the middle class as a group that would dominate the state economically and politically and thus would constitute a new buying public for art. In the decades before the French Revolution, the middle class had made itself known to the artists through the Salon exhibitions, a major cultural event in their time. Although impressed by prestigious history painting, this new class was interested in domestic themed art that reflected their ordinary lives suitable for middle class interiors. If they responded to large works of art or the grandes machines, this public wanted the narratives to be comprehensible and were puzzled by erudite classical themes the artists were rewarded for. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, artists looked, not just to the State for support but also to the patronage of private citizens. Such patronage depended upon the artist obtaining a place in the Salon, gaining notice and finding new collector who would have their own demands. One could dream of making a splash in the Salon, like Jaques Louis David did with The Oath of the Horatii, but the artist was increasingly beholden to the opinions of art critics.

Palazzo Mancini, Rome, the seat of the Académie since 1725. Etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1752)

The artist had to master numerous obstacles to achieve success and make a living from a competitive profession. Most young men began the serious study of art as teenagers and spent years achieving mastery, and the Academy would have been the equivalent of a contemporary high school, dedicated to the arts. The elite training was then, as it is today, the key to success. Any artist who wished to be fêted in the Salon had to go through a set of educational and professional motions, including being trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and perhaps winning the Prix de Rome and then, capping off these student years, with the longed-for recognition in the Salon by the established powers–the State, the Church, and the wealthy patrons. The French Revolution upended the state-based system of educating and rewarding artists, but only for a time. During the Revolution, artists either participated in propagandizing the aims and ideals of the revolutionary cause or risked being denounced and imprisoned by zealots. One of the most important painters for the French Royal family, Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), proved to be an agile and adroit political opportunist and quickly turned his (royalist) coat and put himself in the service of the Revolution. He even went to far as to sign warrants which led to the imprisonment of his colleagues while he designed and built huge works of public art, rather like the Rose Bowl floats of today, that advertized the Revolution and awed the spectators. At the end of the worst part of the Terror, David joined his imprisoned colleagues in the Luxembourg Palace. He was lucky not to have been beheaded–the fates of his sponsors.

Jacques Louis David, Triumph of the French People Over Monarchy, 1793

David emerged from prison somewhat chastened but quickly attached himself to the next rising star, Napoleón Bonaparte, already a patron to Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1825), who had befriended the young general in Italy. David’s pupils, Gros and Anne-Louis Girodet Roussy de Trisson, were able to ride out the Revolution in Italy, safely away from the changing fortunes of artists unwise enough to play politics. But to survive in this inverted world of newly minted leaders, the artist had to be wily to survive. The fin-de-siècle was an age of hero worship and Napoleón rewarded those who worshiped him. Once (relative) sanity returned to the streets and government stability replaced civil war and chaos, the new régime, the Directory, quickly restored the system of art education. The École des Beaux-Arts, the Rome Prize, and all of the academic rules and regulations that, if followed, would lead to Salon success, were all resurrected. But the demands upon the artist had changed. The old aristocratic patrons were gone and new powers awaited the artists. Now governed by a militaristic “man of the people,” the state under Napoleón embarked upon nearly two decades of propagandistic art, celebrating the new Emperor and his court and the glories of war and conquest. Neoclassicism, already an important style before 1789, had been employed as the style of the Revolution by David, who was, under Napoleón, the most important artist of the Empire. Responding to the needs of the new military heroes, Neoclassicism retained its carefully classical style—-clear outlines and cool colors and balanced composition–but was drafted into the service of battle paintings, dramatized and exciting narratives of military exploits, suitable to Napoleónic narratives of victory.

Antoine-Jean Gros. Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau (1808)

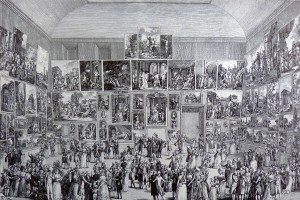

It is here, in these military panoramas, that the germs of Romanticism can be discerned. Early Neoclassicism did not favor diagonals and action and motion, but under the Emperor, excitement and drama ruled and a certain Baroqueness slid back into history painting. That said, the official style of the Empire–bombastic and extravagant–was given over to the same traditional role as had always been expected of artists–supporting the established powers. Although during these Napoleónic years, ideas of Romantic aesthetics from Germany were imported to France, art-for-art’s-sake and artistic freedom were still in the future. The artists had to please new masters, the Emperor, the Salon jury, and the bourgeoisie. Most of all, the artists had to conform to the Salon system itself, now refined and, without the possibility of private commissions from aristocrats, was more important and more competitive than ever. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, the bourgeoisie, was firmly in social, economic, and political power, and despite the comings and goings of various emperors and kings, would remain in power. This middle class was an art-loving class. They knew little about art but knew that they like to be entertained. Thousands came to art exhibitions, the Salons, which were the only avenue of economic opportunity for the French artist who needed to make a living. Scheduled for every year or every other year, depending on which régime was in power, the Salons were huge exhibitions drawing from artists around the world attracted to the prestige of France. Jostling with the French artists, seeking recognition, Americans and British painters and sculptors, not to mention Italians and Germans, pushed into the prestigious contest. Expecting to be delighted and amused, rather like we are pleased (or not) by contemporary film, the French public crowded into the exhibition spaces by the thousands, freely expressing their more or less uninformed opinions.

Salon of 1785

For the French artist, the annual Salon was the one chance to show and to become known. To be refused—rejected from the Salon–was to be a failure, a refusée, until the following year. Merely being accepted was not a guarantee of success. Paintings were hung floor to ceiling and, of course, each painter wanted his/her work to be hung at eye level and not “skied,” that is, hung high, or hung low. Prominent artists could demand that their works be hung where the public could see them easily but those less well known were at the mercy of the installers. The most successful painters were those who pleased both the public and the Academy juries. Sculpture in the Salons adhered to the Neoclassical style but what the audience saw were small-scale works or casts or maquettes for future public projects. Often the smaller works would be placed upon a crowded table and the sculptors suffered from the same kind of limitations to ideal viewing as the painters.

The Salon was a site of hierarchies. History painting reigned supreme, prized because the difficult and didactic compositions, crowded with ancient notables, mostly partially nude, displayed the artist’s erudition and education and artistic skills. Only an artist educated in the École would be capable of drawing and composing a group of figures. Only an artist educated in the École would be educated enough to understand the minutia of ancient history, literary and historical topics favored by the juries. Other artists, especially women, would be confined, due to lack of academic education to lower ranking genres, such as genre scenes and portraiture and still lives, none of which required knowledge of the nude. In these years before modern art galleries and adventurous collecting, the Salon was the only game in town and artists had little choice but to accept the rigorous rule of a conservative elite, disinclined to be open-minded to new artistic ideas. But such new ideas were already present to those who were alert to new styles and new cultural trends. The clash of realism and romanticism was present in the propaganda art of Gros, the blatant eroticism of Girodet stunned the prudish, and the offbeat choice of content by Théodore Géricault, who loved horses and frequented carnal houses disturbed the politically correct. The French Revolution may have ended in yet another oppressive regime under a new Emperor, but it had introduced the idea of individual rights and freedom. Neoclassicism, as a ruling style, essentially ended with the reign of Napoleón, and an artistic revolution that would be called Romanticism began to emerge. Denied political rights and freedom, artists began to resist the demands for the status quo and the edicts issued by the Salon juries and took a more independent path, seeking to attract the attention of the public. Born of political disillusionment, a new attitude began to take shape. The artist demanded the right to freedom of expression as an art maker, which, in these early years of Romanticism, played itself out mostly along the lines of style and the way in which materials were handled.

Both inside and outside the Academy, there was the pressing and urgent quarrel between the Poussinistes (the proponents of line in art and discipline in society) and the Rubenistes (the proponents of color in art and individual freedom in society). This quarrel was a (political) challenge to the dominance of Neoclassicism and the Salon system, which controlled artists. But the quarrel was more than stylistic; it was generational and cultural and political. The dominant art form–controlled and contained Ne0classicism–was connected to the dominant social system, which controlled and contained the populace. These artistic conflicts, no matter how they are labeled, seem to break down into philosophical positions, which seem to extend far beyond any disagreements as to style or subject matter. Neoclassicism vs. Romanticism is really a conflict about emotion vs. reason, which is really a conflict about which should be supreme in art, color (emotion) or line (reason)? The question of line versus color is really a political conflict about who should rule, the people (feelings) or the state (order) were social conflicts concerning democracy vs. the ruling caste. The conflict over individual freedom opposed to the state’s traditional control over the art makers is really a conflict between the lone, romantic genius artist inventing new forms as opposed to the powers of the Academy. During this era, the beaux-arts had a far more important and prominent place in society than today; and the State government of France kept careful control over artistic production, understanding all too well that an artist could speak directly to the people.

Also read: “The French Academy” and “The French Academy: Sculpture” and “The French Academy: Painting”

Also listen to: “The Academy and the Avant-Garde“

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]