Japonisme and Photography

The terms “Near East,” “Far East,” and “Middle East” are all Eurocentric terms because they situate the speaker in the West, assumed to be the geographically superior position, the site from which the imperial gaze sweeps the world. The term “discovery” is another Eurocentric word, such as the “discovery” of America by Christopher Columbus, suggesting that until the explorer bumped into the continent, it did not exist. In a similar fashion, Japan was also “discovered,” accidentally, by Portuguese traders who were lost at sea. For nearly a century, various Japanese daimyo or the feudal lords in power were willing to exchange conversion to Christianity for European guns and an astonishing number of Japanese were converted to the Catholic faith. However, the government power in Japan shifted to a new family, the Tokugawa shogunate, and the trade with Portugal and technological knowledge derived from Dutch and English travelers was a threat to its power. This shogunate, which lasted from 1603 to 1853, is also known as the Edo period or the golden age of Japan’s culture, sought not only supreme power but also a kind of cultural purism expressly hostile to Christianity which placed God above earthly rulers. In 1635, the Tokugawa regime issued an Edict “Closing Japan.” Under Sakoku (closed country), no Japanese ships were allowed to travel to foreign lands and if a Japanese person attempted to visit a Western nation or attempted to return from a forbidden land, death was the result. The members of the warrior class, the Samurai were not allowed to purchase Western goods. The “Southern Barbarians,” the Westerners, were also forbidden to traffic in Christianity. For two hundred and fifty years, Japan was totally sealed off, closed, locked up, isolated.

The isolation ended when “closed” Japan was “opened” at gunpoint by the United States in 1853 under Commodore Matthew Perry. America, barely fifty years from being a colony itself, was not a major player in the Pacific, that role was held by Great Britain. England had its eye on Japan, but, given that it had an important treaty with Hong Kong, “opening” Japan was more trouble than it was worth. America needed Japan as an intermediary way station between its northwest territories and China. England was perfectly happy to sit back and wait for their former colony “open” a territory that had spent so much time in isolation that it now had little importance except as a stop over. But ending the closed door policy of Japan had many unexpected consequences, from the nation’s unexpectedly swift and effective embrace of Western technology to the excitement in Europe and America for all things Japanese, a phenomenon called “japonisme.” Photographers, such as the Austrian expatriate, Baron Raymond von Stillfried-Rathenitz (1839-1911), flocked to the city especially built for Westerners, Yokohama. Once an unimportant fishing village blessed with a suitably deep harbor, the small town became a big city port with Western conveniences installed to accommodate European and American businessmen.

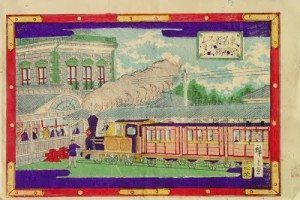

Utagawa Hiroshige III. The opening of the rail line from Tokyo to Yokohama in 1872, an example of kaika-e (pictures of modernization) (1875)

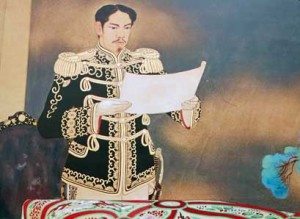

The Opening of Japan for trade and diplomatic relations was less a matter of a forceful or threatening American fleet of gunboats but more a response to internal politics in the nation. Over the centuries, the rule of the Tokugawa dynasty had weakened to the point that the samurai class wanted reform, meaning a powerful group wanted to join the rest of the world and take part in modernity. Under the guise of strengthening the role of the Emperor, a political shift took place during a ten year period and by 1868, the Edo period had come to an end and a Meiji emperor assumed power over the shogunate. The Japanese were well aware of how the British had forced the Chinese to assume a subordinate position as a non-equal trading partner and in the Treaty of Kanazawa (1854) struck a more balanced agreement with the United States and other nations. What makes the Japanese situation unique is that, according to the late Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, Japan was the first “non-white” nation to successfully modernize and absorb Western ways.

The Meiji Emperor in Western Military Dress

In an astonishingly short time, Japan absorbed certain Western political ideas, sought to be educated in the Western manner, and, by the end of the century, was competing with long-standing European powers in the region. The proof of the extent of modernization and industrialization was the Japanese defeat of the Russian Empire in the Sino-Russian War of 1904–05. Japan was the first Asian power to defeat a European power, seizing territory in China claimed by Russia and, apparently incidentally, took over Korea, beginning an occupation that would last until 1945. It is against this background of modernization and Westernization that the Europeans are, in turn, impacted by Japanese aesthetics. Japonisme, a term coined in 1872, when industrialization of Japan was well under way, by a French art critic, Philippe Burty (1830-1890), in the magazine La renaissance littéraire et artistique.

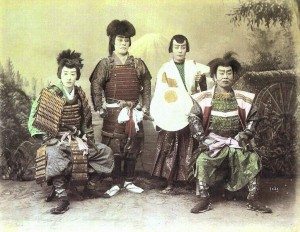

The term, Japonisme, referring to Japan, is slightly different from a similar term Chinoiserie, which refers to China. Chinoiserie is Chinese décor, a style of decoration that had been popular in Europe since the eighteenth century. In contrast, Japonisme is a much broader concept, indicating a strong interest in the broader Japanese culture that would encompass the Ukiyo-e prints of the Edo era, the beautiful silk kimonos, the elegant vases, the graceful fans. In addition, unlike Chinoiserie, the scope and impact of Japonisme was wide enough to inspire Parisian artists, such as the Impressionists, to emulate the abstract designs of the images of the “Floating World.” Artists from James Whistler to Claude Monet not only painted Japanese motifs but also collected Japanese objects. James Tissot pictured women shopping for Japanese vases in a Parisian shop and Mary Cassatt made a beautiful set of prints that emulated the prized Ukiyo-e scenes. The result of the exchange between East and West was a straight-forward reversal: the Japanese received industrial modernization, while the French and the English admired a world whose time had already passed into nostalgia. By the 1870s, the Meiji regime had decisively ended the old feudalistic practices, but incorporating the myths and legends of all things uniquely “Japanese.” Photography in Japan was pure Japonisme on two fronts, first, photographers, such as Stillfried, capitalized on the Western curiosity about a culture previously secretive and obscure by re-creating what were historic customs in the studio and second, because society is more slow to change than politics, photography also grasped the last dying moments of the old days of Edo, extinct politically but remembered socially.

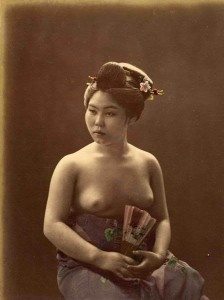

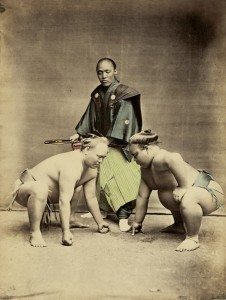

Stillfried worked during the Meiji Period (1868-1912) in Yokohama, an artificial city, and was mostly confined to his studio. Although during the early years of integration, the British controlled the port city, the Japanese guarded their interior. During the early decades of Japan’s gradual integration with the outside world, only a few ports, Tokyo and Nagasaki, along with Yokohama received foreigners and not unit the 1870s and the building of railroads was the restriction of travel outside a twenty-five mile radius loosened. The Japanese who came to Yokohama did so to cater to the Western businessmen and diplomats and must have been in the odd position of being on the front line of modernization but also being expected to respond to Western ideas of what “Japanese” consisted of. The Western culture in these ports was largely male. Only occasionally did a Western woman venture so far afield and the lack of Western women had an impact upon the homosocial environment similar to but different from that of India. Japan was not being colonized, nor was it being ruled by the West, and the relationship was close to that of equals joined together for financial exchange in a capitalist system that was now global. Therefore, the Western men “stationed” in Japan were temporary visitors and, like the soldiers and diplomats “took” temporary or substitute wives, mistresses of color who would be left behind. The Japanese custom of celebrating geishas or women, who were dedicated to the art of serving men, fit very well in the European male’s desire for a subordinated woman, with a dainty woman in a kimono and paper umbrella replacing the previous fantasy of the compliant white slave in an “Oriental” harem. In a gender parallel, Westerners also imagined Japanese men as being part of a warrior class, the honorable and loyal samurai, and photographers obliged local visitors and the overseas market alike with a collection of images that were example of “Japonisme” or a nostalgic version of the Edo culture, recreated for Meiji times.

The extent to which Stillfried’s work must be read as photographic constructions manufactured in a very unnatural context becomes evident when his images are compared to those of John Thomson, who was allowed to roam at will throughout his Chinese territory, where he photographed the Chinese in their natural habitat, living on their own terms. Another telling contrast is that between the studio set-ups staged by Stillfried and the popularity of the “Yokohama” prints preferred by the Japanese themselves. The Yokohama prints were contemporary examples of Japanese artists depicting the Westerners in the city and reveal the Japanese fascination with modernization and especially with the European women, whose presence was overrepresented in these prints. Conversely, Stillfried recreated a vanishing Japan reenacted by compliant actors but Japanese people who actually lived in Yokohama lived in a liminal society and existed on a threshold between history and the future and East and West quickly adopted European clothes and manners, shedding the Edo fashions for frock coats and corsets. It is in the face of the rapid changes clearly visible in Yokohama that the practice of Stillfried can be understand as similar to what Christopher Pinney described in his 1997 work on photography in India, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs, where “a ‘salvage paradigm, which applied to what were perceived to be fragile tribal communities..” But the analogy can be stretched but so far. As Pinney continued to explain: “Official photography was enveloped in a discourse of scienticity and indexicality..” while at the same time altering reality to coincide with Western expectations of the “savage.” That said, Stillfried’s photographs, while faithfully following European desires and predilections, from a need for the exotic to a taste for mile pornography, were not “official” and were strictly commercial, implying but lacking the indexical function.

Baron Stillfried’s predecessor in Yokohama, Félix Beato (1832-1909), founded his business in 1862 and established the convention of “costume” photography and the relatively new practice of hand-coloring the images. Arriving in Japan fresh from his time with the ill-fated Austrian adventure in Mexico, Stillfried purchased not only Beato’s business but the mode of production as well. In her 2011 book, Capturing Japan in Nineteenth-century New England Photography Collections, Eleanor M. Hight described the noble and military background of the Austrian photographer and his experiences as a businessman and then diplomat in the “Far East” and, reading between the lines, it seems strange that a privileged aristocrat in possession of a rare commodity–expertise in Japan–would leave behind such potentially powerful positions in government service of a more precarious private business. But even more oddly, Stillfried was joined in the photography business by his brother, another Baron, Franz. The two brothers, with their military backgrounds, seem to be adventurers, and may have come from a more impoverished branch of the Bohemian nobility. In his article, “Views and Costumes of Japan. A Photograph Album by Baron Raimund von Stillfried-Ratenicz,” Luke Gartlan proclaimed “his imperial credentials as royal photographer to His Austrian Majesty’s Court” and noted that “In acknowledgment of his services in aid of the Austro-Hungarian Expedition, Stillfried received the prestigious Franz Joseph Order on 15 March 1871.” It seems that Stillfried phased out of his service to the Habsburgs, was decorated for his work and became a commercial photographer. As was discussed earlier, Yokohama was a city where Western men of means could build their own private fantasies of living in a harem of Japanese women and, over time, Stillfried had become so accustomed to the geisha way of life that he made the mistake of transporting it to Vienna, a city remarkable for its sexual repression. As Gartlan recounted, “Eager to expand his enterprise, he transported a seven-room Japanese teahouse to Vienna for the World Exhibition and contracted three Japanese women to serve tea to the Viennese public. Accused of managing a bordello under the guise of an ethnographic display, Stillfried returned to Yokohama near bankruptcy, his reputation tarnished by the entire sordid affair.”

Stillfried worked in Japan until 1881, producing photographs as souvenir, whether sold individually to tourists putting together collections of mementos or as elegantly bound albums that he had composed into a single volume. Building on a combination of his own technical ability as an excellent photographer, he commanded a large staff of local workers. The handsomely bound albums with their elegant metal clasps were inscribed in English, the international language used in China and Japan. The aristocratic and educated background of the photographer is evident in his studio studies of pre-modern Japan. Some of the images are in the tradition of portraiture while others are reminiscent of genre paintings, scenes of everyday life. And indeed, there are intimations of class distinctions imposed upon an Asian society. Stillfried’s recreation of “types” in old Japan cannot be said to be anthropological studies of an existing society but as examples of Japonisme, the photographic equivalent of the Ukiyo-e prints of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, for example. Frozen in front of studio backdrops, imprisoned beneath dedicated hand-applied colors, the Japanese actors play on a stage catering to a kind of Western curiosity that does not require information but satisfaction of imperial desires.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.