NEO-CLASSICISM IN FRANCE

The Early Years

In any academy, whether from the seventeenth or the eighteenth or the nineteenth century, history painting was the most elevated form of painting due to the designated “important” themes treated by the artists. In terms of the hierarchy of genres or the preferred and most prestigious forms of painting and sculpture, historical topics were favored over scenes of the present, genre scenes, landscapes, or portraiture. The “history” depicted, where actual or mythic or religious, consisted of events the dominant culture considered significant and that were, therefore, considered by the authorities, topics suitable for public consumption and social edification. The content of history painting was the most difficult for artists to paint, for the complex compositions with multiple human figures were given (or selected) in order to display the artist’s knowledge of anatomy, range of academic artistic techniques and command of erudite history itself. Such intellectual knowledge could be gained only at art schools or the Academies where all students were taught in an “official style,” which, for decades in France, had been the grand Baroque manner of Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665). Although Poussin had spent his career in Rome, he was revered in his native land, France. But by the middle of the eighteenth century, the Baroque style was exhausted. In architecture and in interior décor and private commissioned painting, the Baroque had evolved into the soft and erotic Rococo style, leaving the “grand style” for the State and its advertisement.

Nicolas Poussin – Et in Arcadia ego (deuxième version (1637-38)

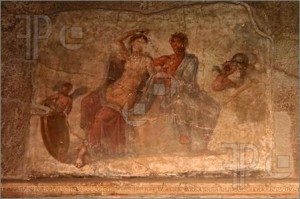

For Enlightenment thinkers, such as Denis Diderot, it was time for a new style, one that would better reflect the needs of a changing society. An artistic revolution to put an end to the grand manner of Poussin and the sensuality of François Boucher (1703-1770) was needed. In the middle of the century, Herculaneum and Pompeii, towns buried by a long forgotten eruption of the volcano Vesuvius in 79, were discovered in 1738 and 1748. These towns were resort towns near Naples and were favored by well-to-do Romans in the early Imperial era. Frozen in time, magnificent villas were unearthed, revealing extraordinary murals painted by provincial artists. Beyond Greek vases, no substantial examples of classical paintings were extant until these towns were re-discovered. Suddenly the linear and simple approach to drawing and the cleanly painted areas of strong colors provided a new way to make art to a young generation of artists who wanted to make their marks in the Academy and upon new patrons. The linear approach of the Pompeiian murals and their strong colors, similar to Greek vases, were an antidote to the showy brushy painterly styles so prevalent with the Rococo. The affinity to the simple compositions and strong lines of Poussin made it easy to assimilate the paintings of Pompeii for artists who were interested in being radical, a prospect that took four decades to come to fruition.

Classical Black Figured Amphora with Achilles and Ajax Playing Dice

The unearthing (and looting) of a slice of ancient life, preserved in its original state had a revolutionary impact upon the visual arts, from drawing to painting to interior design to architecture. The clean hard edges of the antique drawing style stood in strong clear contrast—even a stern rebuke—to the soft edges of the waning Rococo style–or so it would be understood within the political context of social unrest and the coming of the French Revolution. The modern version of the Antique Style was coded in the mid-eighteenth century as “simplicity and virtue,” while the Rococo style was coded as “corrupt and decadent,” a class distinction with political overtones. The result of these new discoveries in Italy was an International adaptation of classical art was what the art historian Hugh Honour called the “cult of antiquity,” developed to reflect the needs of each country, whether England or France or Germany, inspired by this “neo” “classicism.” These anachronistic and political readings imposed upon Classical art as “virtuous,” happily ignoring mystery paintings or scenes of sheer pleasure, were filtered through a newly powerful middle class and the bourgeois art public, seeking to forge a new identity in opposition to the aristocrats.

Wall Painting from Pompeii

Dating from 1760 to 1800, the Neoclassical period begins with an air of expectancy, as though an era is awaiting a Messiah. The co-author of the Encyclopédie, Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, Denis Diderot yearned for the artist who could correct the excesses of the Baroque and the decadence of the Rococo, but he did not live to enjoy the work of the artist, who would inflict upon these old styles the coup de grâce, Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). Neoclassicism is more than a simple shift in artistic style or in audience taste, the style became a vehicle for conformity or rebellion, for the erotic or the political, depending upon the artist in question. The fact that this ancient style proved to be so flexible and contradictory is explained by its placement in time—in the midst of vast economic and social changes, with intimations of a “return” to the foundations of European culture so that a new society could be built upon the old values. Neo-classicism was ideally suited to a new “grand” style that could supersede the Baroque and re-inject a new seriousness into history painting.

The fact that a philosopher and a thinker such as Diderot was also an art writer, corresponding with the crowned heads of Europe, attests to the increasing importance of art as a mode of communication of social ideas. Towards the end of his career, Diderot favored Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) an artist who depicted calm and sober middle class life. The quiet industry of the bourgeoisie was a strong contrast to the luxurious and useless lives of the French aristocrats and in retrospect we can read political changes if not overt political statements in the contrasts of grand Baroque, decorative Rococo, and austere and quiet middle class art. Because it was “new,” Neoclassicism became the vehicle for an artistic style upon which emerging social and cultural needs would be projected. Inspired by classical antiquity, artists painted with archaeological exactitude, based upon historical research and actual trips to Italy. The Neoclassical style was one of intellect, an art of perfecting nature and of presenting idealized human forms and exemplary human behavior. As such, Neoclassicism can be thought of as the application of a theory of aesthetics, a new definition of art as an attempt to re-write social existence and as a text suggesting a new world of improved human behavior.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin Woman Cleaning Turnips (1738)

Initially, Neoclassicism reflected the interests of the upper class, its passion for collecting the rare and precious antiquities and its need to present an ennobled self-image to a world, increasingly disenchanted with the self-indulgent ways of the aristocracy. But it was the aristocracy itself that provided the first and most enthusiastic market for Neo-classicism. The market orientation of Neoclassicism is most obvious in the early stages of the style with the frozen eroticism of Joseph-Marie Vien, but this fascination with the eroticized female would be ended by the second stage of Neoclassicism, and heroic men would take the center stage as active and noble subjects. Monumentality and sober and serious colors, strong shadows and theatrical settings filled with brave men engaged in virtuous enterprises became the preferred style at the end of the Eighteenth Century. David’s conversion to Neoclassicism in Rome, as seen in The Oath of the Horatti, 1785, resulted in a style that could serve the needs of his King as well as the needs of the Revolution that followed. Neoclassicism’s ancient roots rendered it universal and suitable for a multiplicity of causes and purposes.

****

In its early stages, Neoclassicism was first a period of response to art of antiquity. As seen in the art of a French artist, Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809) and a Swiss artist working in England, Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), Neoclassicism is basically a reform of the Baroque with classical subject matter as the major content. Both artists presented a parade of antique characters, mostly women, wearing attractive Greco-Roman gowns, engaged in ordinary everyday activities. Introducing Neoclassicism to the French in the Salon of 1763, Vien presented an antique version of the Rococo, meaning that his work is linear, inspired by John Flaxmann’s (1755-1826) line drawings of Greek vases, but that his content is erotic, inspired by Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s (1732-1806) boudoir paintings. It is perhaps in England that the link between Neoclassicism and the Enlightenment can be most clearly seen. In her 2004 book, Geometries of Silence: Three Approaches to Neoclassical Art, according to Anna Ottani Cavina, John Flaxman followed the dictates of the theorist of the Neoclassical, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) who said, “Let the artist’s pencil be impregnated with wisdom.” In its philosophical challenges to the age of monarchs, the Enlightenment stressed the importance of human reason and individual intellect. But most of all, the Enlightenment introduced the concept of rigor in thinking and logic in theory, making it a thoroughly middle class philosophy that prized individual humanity. In an homage to middle class ideals, Kauffmann created genre scenes out of the classical era, domesticating and gendering Roman virtue, and celebrating the ethics of women. The patrons for these artists were aristocrats who liked to keep up with the latest art trends, but what is interesting in the case of these early Neoclassical artists is that these artists produced stories of everyday life, rather than serious history painting, and that these paintings were clearly destined for a domestic rather than a state setting.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Neoclassicism would be come serious and history painting, reconfigured to accommodate a new trend in subject matter. Baroque art had been a grand form of propaganda for state power, an advertising style, as it were. Neoclassicism would present another theme: the morality of civic life and the artists would seek a more didactic content in order to teach the art audience, the public, the citizens of the state, how to live ethical lives. The final break from the Baroque to the Neoclassical came in the art of Jacques-Louis David, who was “converted” from the grandeur of the older style to the austerity of the classical when he was sent to Rome by the French Academy. That said, David’s art was as rooted in the patronage of the aristocratic class as was that of Vien and Kaufmann. The distinction between the first and second stage of Neoclassicism was the move to large sized history paintings intended to announce the advent of a newly important style. There was, as was noted in an earlier post, a gap in the rediscovery of antique art and its appreciation and the full development of a Neo-classical style that eventually happened in France. Part of the slow shift towards a new style in France had to do with a lack of appreciation of a native French style.

According to Colin B. Bailey in his book Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pre-revolutionary Paris, the pre-Revolutionary French collectors preferred Flemish and northern artists, until the 1780s. As Bailey wrote, “By the middle of the eighteenth century, the preference of Parisian collectors for Italian and Northern old masters was being questioned for the first time by critics and amateurs eager to promote the French school.” Bailey noted that the abbé Louis Gougenot, who liked Greuze, “lamented” that the only place to see French painting was in the biennial Salon: “To the shame of our Nation, and to the astonishment of foreign visitors, our so-called art lovers–attracted by the unusual rather than the truly beautiful–make it an unwritten law to banish the work of modern painters, no matter how good, from their collections.” The point is an important one, as it is adventurous patrons who made Neo-Classicism important and accepted in Paris and in the French Academy.

There is an important prelude, therefore, to the success of David and his new style that was a result of the increasing demand that French art be foregrounded in Paris. Collectors began heeded the call to turn their serious attention towards living French artists. Joseph-Hyacinthe-François de Paule de Riguad, the comte de Vaudreuil, of the Ancient Régime, as Bailey pointed out, was an important early supporter of David, although through art historical prejudice, he has been discounted due to his association with Elizabeth Viegée-Lebrun. But what connects the two disparate artists was that they were both living and important French artists, supported by new patrons. It is often assumed that suddenly Rococo art disappeared as soon as Neo-Classicsim hove into view, but such is not the case. As Anne L. Schroder in “Reassessing Fragonard’s Later Years: The Artist’s Nineteenth Century Biographers, the Rococo, and the French Revolution” noted, Fragnoard did not descend into disgrace, but continued to thrive through the private market that still had a taste for Rococo art and was, in fact, a close associate of David himself. As she pointed out, the Rococo style never faded away and was beloved to the extent that during the Second Empire, it–not Neo-Classicism–was seen as the true national style of France.

Jacques Louis David. The Oath of the Horatii (1785)

David’s career and success was, in fact, based upon the pre-Revolutionary desire to promote “French art.” The most important power who as behind a larger effort to put French art before the public was Charles-Claude Flahaut de la Billaderie, comte d’Angiviller, who was the director of the Bâtiments du Roi. According to Andrew McClellan in his 1994 book, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-century Paris, was responsible for renovating the Grand Gallery of the Palace of the Louvre into “a space suitable for the public display of art.” Working under a crumbling and indecisive Louis XVI, de Vaudreuil had ambitious plans for the Louvre, even “anticipating the modern museum in which the objects on display are allowed to speak for themselves, de Vaudreuil insisted on only minimal decoration of the gallery’s walls and ceilings. Even the new frames ordered for the museum were characterized by elegant, neoclassical restraint.” This was the influential man who would be the supporter of Jacques Louis David–one could hardly get closer to the throne of France than the aristocrat who was stocking the Louvre with the works of living artists.

In one of the first modern art historical studies of Neoclassicism in 1967, Robert Rosenblum’s Transformations in Late Eighteenth-Century Art, attempted to sort out the many variations of Neoclassicism. For France, during the transition out of the monarchy, into the Revolution, and transiton towards the Empire, what Rosenblum called “Neoclassic stoic” suited a country in turmoil. It was the comte d’Angiviller, who commissioned David to do a grand history painting, using as theme from the Roman Republic to suggest loyalty to the King. David chose a scene from the story that was slightly different from the one requested, but the “oath” to the patriarch, the father, the leader of the tribe, fell within the parameters of his patron’s requests. The Oath surprised the Parisian art audience, not by its subject matter but with its rigid classicism, a revelation of austerity in comparison to the widely loved Rococo. Following the shocking debut of David’s Oath of the Horatti in the Salon of 1785, Neoclassicism quickly became the favored style of the French Salon. As Rosenblum stated, Neoclassicism “looked toward antiquity for examples of high-minded human behavior that could serve as moral paragons for contemporary audiences.” This particular manifestation of Neoclassicism could serve the ancien régime and the Revolution and the Empire with equal efficacy.

Moving from its second stage as a spare and Spartan style of rigor, Neoclassicism’s third state was activated dynamic one, in the service of Napoléon in France. Formally speaking, Napoléonic Neoclassicism was a dynamic or diagonal repositioning of the horizontals of the Stoic phase. A comparison between David’s Death of Socrates (1787) with his Napoléon Crossing at Saint-Bernard (1801) shows the same linear effects, block colors, strong and deep hues, and shallow stage-like setting, linked to relief sculpture and vase painting. David’s works always have the look of a tableau-vivant or pantomime play and his classical style seemed to consist of frozen postures, static and unnatural poses and overtly theatrical scenes. Later, in the early nineteenth century, Neoclassicism softened due to the new tendencies towards the prelude to Romanticism, as seen in the work of Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781) (Johann Heinrich Füssli), Anne-Louis Girodet (de Rossy-Trioson)’s The Sleep of Endymion (1791),and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Dream of Ossian (1813).

And finally, Neoclassicism dwindled down to a final stage of a sugary, sentimental, pompous, and empty academic style, demanded of their students by the powers of the Academy. Even David fell victim to the final spasms of a dying style and he and his pupil François Gerard produced a series on the lives and loves of Cupid and Psyche. Neoclassicism, exhausted as a means of communicating powerful ideas, became the academic status quo enforcing the established powers and becoming a retrograde style against which avant-garde artists will fight. At its height, Neoclassicism was the dominant art style, restrained, cool and formal, marked by moralistic themes and perfect for the new forms of government following the fall of the French monarchy. By the time the nation had undergone the traumas of a Revolution and an Empire and a Restoration, the Enlightenment optimism embedded in Neoclassicism gave way to Romanticism, a dramatic style that could express those traumas and disillusionment.

Also read: “French Neoclassicism: Sculpture and Architecture” and “French Neoclassicism” and “The Origins of Neoclassicism”

Also listen to “Neoclassicism” and “Jacques-Louis David”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]