Irish Artists at War

Part One

John Lavery (1856-1941)

Apparently Sigmund Freud never said of the Irish, “This is one race of people for whom psychoanalysis is of no use whatsoever,” but the idea that it is pointless to attempt to fathom “the Irish” has implanted itself in popular culture. But true or not, the not-quote by Freud begs the question: who are “the Irish?” The indigenous Irish, who were left strictly alone by the Roman Empire and overlords of England, were Celts from Iberia, an origin that distinguished them from the Celts of southern England who were Germanic. Only marginally disturbed by visiting Danes, the wild Irish tribes were “civilized,” i.e. Christianized, by Saint Patrick, but they continued their warlike contentious habits, going to battle in a perilous state of nudity. However, internecine conflicts among contending kings left the dis-united territory ripe for conquest from the neighbor across the sea. Under Henry II, the Normans colonized Ireland in 1171 and established rule over a territory called the English Pale, a rather small chunk on the Western edge which encompassed Dublin. For centuries, following the Plantagenet practices, the English rulers rewarded their vessels with Irish land, giving away large dominions that were often neglected by the absentee landlords.

Under Elizabeth I, the Irish were also expected to forego their Catholic beliefs and become Protestant, like those who lived in the English section of Ireland. Once converted by Saint Patrick, the Irish would not be reconverted, and became, in the eyes of the English rulers, enemies who would align themselves with Catholic powers. Four hundred years of religious persecution followed. Having firmly rejected the Anglican faith, the Irish were inspired by the American Revolution and dreamed of throwing off British dominance. For the British, the Irish were inferior savages and the colonizers created terms for the Irish that became the bedrock for racist language that would be transferred to America. As late as 1988, a member of the British parliament referred to the Protestants in Ireland as the “white people.” In 1910, on the eve of the Great War, Irish were thought to be “excitable,” emotional, lazy drunks, good with music and dance, but angry people, who “got their Irish up.” They were “Paddies,” a reference to Saint Patrick and they were also the weak “feminine” to the “masculinity” of the the overlords. The English had such contempt for this inferior race, they allowed the Irish to starve during the devastating years of the Irish Potato Famine. The lucky ones were able to immigrate to America where they were met by imported English prejudices. Those who somehow survived the famine stayed behind to repeatedly rebel agains the hated colonizers.

Literally days before the declarations of war in August of 1914, the Third Home Rule bill seemed poised to allow the Irish to govern themselves, if only under the umbrella of Great Britain. But the War put Home Rule on hold once again and it is with the current cloud of bad feelings that the English attempted to convince the Irish, Catholics and Protestants alike, to enlist in the conflict against the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires. To be Irish and to be at war in 1914 meant serving with the British and supporting the English cause against the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires. To be Irish means to be in a divided nation, torn between Catholics, the colonized inhabitants of Ireland, and the colonizers, the English Protestants. But over 100,000 Irish men volunteered to serve their country or Great Britain or to prove their worthiness for home rule. The leader of the Irish Party and Minister of Parliament, John Redmond stated that, “The interests of Ireland – of the whole of Ireland – are at stake in this war.” Some wanted adventure. A future leader of the Irish Republican Army, Tom Barry, said that he enlisted “for no other reason than to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel like a grown man.” Other men, living in poverty, simply needed the money. By all accounts the Irish fought bravely. In fact the London Irish Rifles became national heroes at the Battle of Loos in 1915 when Sargent Frank Edwards led a group of Irish soldiers who kicked a soccer ball over No-Man’s Land to the enemy trenches. Although there are doubters who think the episode has become more myth than reality, the football still exists (or so they claim) and there are accounts written at the time:

Suddenly the officer in command gave the signal, “Over you go, lads.” With that the whole line sprang up as one man, some with a prayer, not a few making the sign of the Cross. But the footballers, they chucked the ball over and went after it just as cool as if on the field, passing it from one to the other, though the bullets were flying thick as hail, crying, “On the ball, London Irish,” just as they might have done at Forest Hill. I believe that they actually kicked it right into the enemy’s trench with the cry, “Goal!” though not before some of them had been picked up on the way.

The Irish artists who responded the war included the poet W. B. Yeats (1865–1939), who wrote “An Irish Airman Foresees his Death.”

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan’s poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

Despite the prophetic nature of the poem, at the time of its writing, Yeats was not an airman, he was at mid-life and feeling his age. The poem needs to be read as an expression of the Anglo-Irish poet’s Irish nationalism and as part of his decades-long attempt to revive and incorporate the Gaelic rhythms of a Celtic language fading into memory. Like Yeats, the great illustrator of the Royal Navy during the Great War, Sir John Lavery had a mixed ethnic background, incorporating the Irish, Scottish and English cultures. While Yeats had fought all his adult life as a creative artist to promote all things Irish, Lavery had been a successful society artist, painting fashionable portraits of the English rich and powerful in an appealing post-Impressionist style. The Great War was a call to arms for the Irish artist who, although, like Yeats, was middle-aged, and determined to record the conflict on the Western Front. His plans to join his friend and fellow artist, William Orpen, in France were literally blown apart when a Zeppelin dropped a bomb on London, causing his automobile to wreck. Injured, Lavary was no longer able to work safely in a combat zone. Appointed an Official War artist in 1917, the sixty-two artist had what the

National Galleries of Scotland describe as “a roving brief to depict naval bases around Britain.”

Sir John Lavery. A Misty Day, the Firth of Forth (1917)

Although Lavery worked on the South Coast of England, recording the activities of the Royal Navy, his most famous paintings were done on the freezing north coast in the ports of Scotland. The German fleet challenged the British in the North Sea and the Imperial Navy surrendered on the Firth of Forth in 1918. Lavery was in place to depict that significant event, completing the humiliation of Germany at the hands of the English.

Sir John Lavery. The End: The Surrender of the German Fleet, 16 November 1918 (1918)

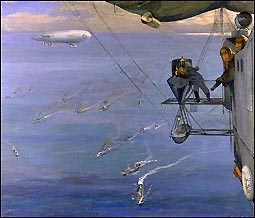

Ironically, having been the victim of a bombing, Lavery did one of his most dramatic paintings from the cabin of a British airship, floating quietly above a convoy traversing the North Sea. The airships, the British version of the German Zeppelin, were used to search for signs of a lurking submarine and were safe enough to allow the artist to go along for the ride. However, unlike Christopher Nevinson and Paul Nash, for example, Lavery’s assignment kept him at a distance from the War itself. In part, the choice of panoramic views of naval installations, was due to censorship. The Chief Naval Censor gave him special permits which allowed him to do what were essentially landscape paintings which gave away no essential information to the enemy.

Sir John Lavery, A Convoy, North Sea (1918)

In 1919, Lavery, recovering from his exhausting war work, had donated his substantial body of his paintings to the Imperial War Museum and visited the vast cemetery at Étaples. Near Boulogne, this small town on the Paris-Boulogne railroad line was home to a complex of reinforcement camps, a dozen Red Cross hospitals, and a conversant depot, still occupied by the wounded when Lavery visited the cemetery continuing over ten thousand graves. He showed the endless lines of graves, marked by crosses, which did not distinguish between Catholic and Protestant, tended by small groups of women in black dresses. Beyond the freshly turned earth, the land is green in the distance, a peace penetrated by a long black train, puffing white smoke.

Sir John Lavery. The Cemetery at Étaples (1919)

A year ago, trains had arrived from the front four times a day, bearing wounded to this territory, lodged between a fishing village and the railroad. Lavery was suddenly confronted with the reality of the war, a conflict he had viewed from afar and on high. He had extensively illustrated the important war work done by women in factories and in hospitals. And yet he had somehow missed the War itself. He explained his reaction to the buried lives of thousands of young men who had died for their country: (I) “felt nothing of the stark reality, losing sight of my fellow men being blown to pieces in submarines or slowly choking to death in mud. I saw only new beauties of colour and design as seen from above.” He later brushed aside his wartime art as “dull as ditchwater.”

And yet, Lavery was an interesting character, who, like Yeats, was a strong supporter of the Irish cause, thanks to his second wife, Hazel, a beautiful Irish-American patriot and painter in her own right. Educated at the Académie Julian in Paris, he had a strong foothold with the rich and the powerful of England, where he used his neutral and uncontroversial style to depict the well-born at their leisure. Although he was close friends with James Whistler, his pre-war art is more akin to James Tissot. After the War, without missing a beat, Lavery resumed his studies of the upper classes, as if the catastrophe never happened.

Viewing his art is rather like visiting Downton Abbey, and, as with the multi-year television series, we are able to be witnesses to the changing lifestyles and fashions of the ruling class. But there is another side of this artist. Lavery, now “Sir,” and his wife were important fixtures on the London social scene, navigating the treacherous waters between the Irish and the Anglo sides. Hazel taught Winston Churchill, a close friend, to paint, and the British government, represented by the judge Sir Charles John Darling, trusted Lavery enough to commission a painting of a very controversial trial of an Irish advocate for a rebellion against England, Roger Casement.

Roger Casement had turned to the German government for support of the Irish Nationalist rebellion in Dublin in the Easter uprisings of 1916. Casement had actually been knighted in 1911 for his services in the cause of human rights in the colonies, but his trip to Berlin with the aim of freeing Irish prisoners so that they could participate in the planned revolt ended in his being taken prisoner off the coast of Kerry. Stripped of his knighthood, Casement was imprisoned in the Tower of London under the charge of high treason. There were those who were inclined to be sympathetic to a political prisoner until the government published his private diaries, which revealed that Casement was a homosexual. Every day Lavery attended his trial, sketching on a concealed notebook the courtroom scene that contained over three dozen portraits. Some accounts of his life suggest that Lavery had pro-German sympathies or that this painting was courageous, but the painting looks and functions as a mainstream commission, possibly a co-option by the government of a prominent Irish couple known to be interested in Home Rule. In a long speech he gave before he was hanged, Casement said,

“Loyalty is a sentiment, not a law. It rests on Love, not on restraint. The government of Ireland by England rests on restraint and not on law; and, since it demands no love, it can evoke no loyalty. Judicial assassination today is reserved only for one race of the King’s subjects, for Irishmen; for those who cannot forget their allegiance to the realm of Ireland.”

There is every reason to believe that this trial, a painful episode in the midst of an unsettling war, had a profound effect upon Lavery. The judges and their mission to mete out justice are not the focal point, but the defense and Casement himself, considered today by many to be a martyr. According to Fintan O’Toole, writing for the Irish Times,

Roger Casement wrote to his family, asking, “Who was the painter in the jury box?” Yet, as Casement noted, the painter “came perilously near aiding and comforting” the prisoner in the way he “eyed Mr Justice Darling’s delivery” of the verdict confirming the death sentence. Casement also noted that Lavery’s wife, Hazel, looked “very sad” at the same moment.

Sir John Lavery. High Treason: The Appeal of Roger Casement (1916)

The painting itself, measuring seven by ten feet, apparently did not please Darling. There is some suggestion that perhaps the judge had not even commissioned the group portrait, but it is unlikely that the artist would have been allowed in the courtroom if that were not the case. That said, the painting seems to be have been painful for both the artist and England. Perhaps interrupted by his duties as War Artist, Lavery did not complete the work until 1931, by which time no English institution would accept the painting. Neither the National Portrait Gallery and the Royal Courts of Justice were prepared to exhibit it. For years it hung in an office of the Gallery until it was transferred to the Honorable Society of King’s Inns in Dublin on an indefinite loan. The painting was not put on public display in England until 2003.

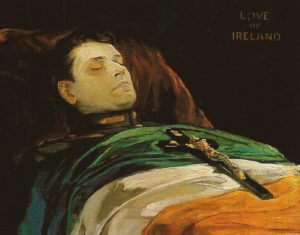

Sir John Lavery. Michael Collins Lying in State. Love of Ireland (1922)

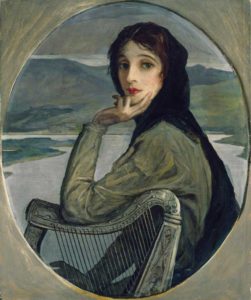

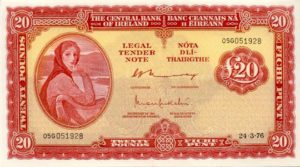

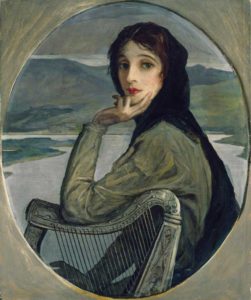

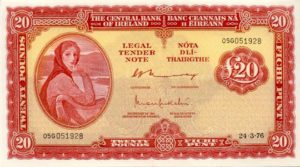

But it is Hazel, born in Chicago, who is best remembered by the Irish for her tireless work in reconciling the Irish and the British. Half her husband’s age, she persuaded him to paint prominent Irish politicians and even had affairs with more than a few of them, including, or so they said, the famous patriot, Michael Collins (1890 – 1922), who supposedly died with a letter from her in his pocket and a miniature of her portrait hanging from his neck. The two may have grown too close when the Lavers had lent their London home to the Irish delegation during the negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. For the Irish Republican Army the treaty was nothing short of a betrayal and arranged for an ambush assassination of their former leader in his homeland in County Cork. Although Lady Hazel attend his funeral draped in black, signifying widowhood, her husband, Sir John painted the fatally wounded Collins on his deathbed. Although the IRA was suspicious of her sentiments, Hazel survived to serve as the face of Ireland on an Irish banknote for the new Irish Free State. The image is based upon a portrait of her as “Cathleen ni Houlihan,” a character in a play by her friend William Butler Yeats, painted by her husband.

Until the 1970s, Hazel Lavery, Irish-American hero, as depicted by her husband, Sir John Lavery, former Official War Artist, famous portraitist to the powerful, smiled out from the face of the Irish bank note, as the allegory of the spirit of Ireland itself.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.

[email protected]