THE DAGUERREOTYPE

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851)

“I am burning with desire to see your experiments with nature,” Daguerre wrote to Niépce in 1828. The partnership of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and Jacques Daguerre was an unlikely one. Niépce was a dedicated tinkerer and amateur scientist, and Daguerre was a man of the theater, a well-known scenic designer and a painter who showed in Parisian Salons. It is known that he was experimenting with some form of photography at the same time that Niépce was shopping for new lenses at the optical firm of the Chevaliers, father and son nicely located at the Quai de l’Horloge. It was Vincent Chevalier, the father, who put the scene painter, then was using the camera obscura for his work as a scenic designer, in touch with the inventor. The two men carried on a correspondence over time, while they both worked independently. It was after Niépce came back from his unsuccessful attempts to interest the British in his photographic process that the two very different men formed a partnership in 1829. Niépce had already produced a unique positive on a pewter plate after an eight hour exposure. By placing a camera on the window sill of his home in La Gras, he captured a series of roof tops in an image that was wholly “documentary,” meaning that he had no artistic intent. Niépce was an experimenter, not, like Daguerre, an artist. In the same year he formed his partnership with Daguerre, Niépce published an account of his process,

The discovery which I have made, and to which I give the name heliography, consists in producing spontaneously, by the actions of light, with gradations of tints from black to white, the images received by the camera obscura. Light acts chemically upon bodies. It is absorbed ;it combines with them; it solidifies them even; and renders them more of less insoluble, according to the duration of intensity of its action. The substance which has succeeded best with me is asphaltum, dissolved in oil of lavender. A tablet of plated silver is to be highly polished on which a thin coating of the varnish is to be applied with a light roll of soft skin. The plate when dry may be immediately submitted to the actin of light in the focus of the camera. But even after having been thus exposed a length of time sufficient for receiving the impressions of external objects, nothing is apparent to show that these impressions exist. The forms of the future picture remain still invisible. The next operation is then is to disengage the shrouded imagery, and this is accomplished by a solvent, consisting of one part of volume of essential oil of lavender, and ten of oil of white petroleum. Into this liquid the exposed tablet is plunged and the operator observing it by reflected light, begins to perceive the images of the objects to which it has been exposed, gradually unfolding their forms. The plate is then lifted out, allowed to drain, and well washed with water.

Already in his sixties, Niépce had only a few more years left to live and he may have sensed the need to hand his work off to someone younger, more energetic and more entrepreneurial. Daguerre was a solidly established artist and set designer, in favor with the current regime and sure-footed in politically perilous times. Like most business people in Paris at this time, he was in and out of bankruptcy, as the economy rose and fell. In addition, he was in and out of partnerships because most businesses at this time were self-financed. Without the private funding available to the wealthy Niépce family, Daguerre’s interest in photography was purely commercial or to be more precise he wanted to put the invention, once it was perfected, to good use in monetary ventures. Only a few examples of his photographic work survived, but it seems clear that Daguerre was interested in the process largely for its practical use as a recorder of reality through the activities of light. And Daguerre knew about light.

Daguerre’s painting, using a camera obscura, based on a diorama

Daguerre was the owner and designer of a company that produced dioramas shown in his Paris Diorama which sadly burned down in 1839. The Diorama was a three hundred and fifty seat building constructed at 4 rue Sanson expressly for the display of two dioramas, which the audience, sitting as if in a theater, viewed painted scenes that, due to the actions of light itself, seemed to be moving and changing. The natural light could be manipulated by blinds and colored screens to mimic the effects of night and day. The platforms that supported the thin paintings rotated so that the audience could view more than one scene at a visit. Daguerre created a collection of paintings, sometimes of contemporary events, that could be changed to keep the audience returning, as if to a theater to watch a new play. These large panoramic painted backdrops, measuring 71 x 45 feet had human figures interacting in the scenes but the figures were visible only when the light was set in a certain way, so that the scene could serve dual temporal and narrative purposes. The “actors” or characters could come and go or appear and reappear with the lighting effects. These panoramas often showed up elsewhere as actual paintings which Daguerre showed at the official Salons to maintain his reputation as a serious artist.

Daguerre’s Diorama Theater 1830

But the camera obscura was his constant partner at achieving his magical effects. Daguerre even experimented with phosphorescent materials in order to achieve an incandescent effect which he could then duplicate on the stage. When Niépce visited Daguerre at his Diorama in Paris in 1827, the two men formed a partnership in 1829, combining the theatrical work of Daguerre with the camera obscura and the work of Niépce with bitumen of asphalt. And by combining his own experiments with his work with Niépce, who died in 1833, Daguerre was able to create a far superior image, which he, in his characteristic self-promoting manner, called “the daguerrotype.” Although he had signed a new contract with Niépce’s son Isidor, Daguerre claimed to be the “inventor of the daguerrotype,” infuriating Isidor. The implications of the “first” “daguerrotype” are murky. Contractually, Daguerre laid claim to the process, which could be interpreted as distinct from the object itself, already invented or achieved by Niépce. Isidor wrote a rebuttal to Daguerre’s claims but his remarks was published too late in 1844 to make a difference. The long title was hardly inviting but it was direct: History of the discovery improperly called “daguerreotype” preceded by a notice of the real inventor, the late M. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, by his son, Isidor Niépce.

Not withstanding the opposition of Isidor, Daguerre announced his invention on several occasions, first in 1834 and then in 1835, he printed his account of the invention in the Journal des artistes in September 1835. These early announcements were apparently part of a campaign on the part of Daguerre to raise money to finance his new invention but he found no interest in his work. It would seems that at this time, Daguerre gave up and turned the daguerrotype process to over the French people as a gift to the public. His experimental work was supported by a deputy of the Académie des Sciences and Académie des beaux-arts, Dominique-François-Jean Arago (1786-1853), who made an official announcement on behalf of the French government in August of 1839, saying that it was “…indispensable that the Government should compensate M. Daguerre direct, and that France should then nobly give to the whole world this discovery which could contribute so much to the progress of art and science.”

Arago was interested in the daguerrotype, which was a production of light, because he was involved in experiments with light itself. It was he, working with Augustin-Jean Fresnel, who discovered that light was composed, not of particles, but of beams in 1811. At the time of the announcement of 1839, Arago was trying to prove that light moved in waves, a project that was not completed (proven) until after his death. He actually contributed some of the funding for Daguerre and was a patron of the photographer at the time of the 1839 announcement. The daguerrotypes made available for the members of the Academy are no longer extant but the images apparently consisted of a photograph of a spider photographed through a solar microscope and a view of the moon that astonished everyone. Reassured of some monetary compensation, Daguerre released the details of the daguerrotype process to the public at the end of August. In the on-line book, A History of Photography from its Beginnings until the 1920s (1995), Robert Leggat described the process and defined the daguerrotype as

First, exposing copper plates to iodine, the fumes forming light-sensitive silver iodide. The plate would have to be used within an hour exposing to light, between 10 and 20 minutes, depending upon the light available developing the plate over mercury heated to 75 degrees Centigrade. This (exposure) caused the mercury to amalgamate with the silver fixing the image in a warm solution of common salt (later sodium sulphite was used). Finally there was a rinsing of the plate in hot distilled water.

The result was a unique positive image on a silvered place, that could not be reproduced but the image was extremely precise and clear. As Leggart explained,

..the pictures could not be reproduced and were therefore unique; the surfaces were extremely delicate, which is why they are often found housed under glass in a case; the image was reversed laterally, the sitter seeing himself as he did when looking at a mirror. (Sometimes the camera lens was equipped with a mirror to correct this); the chemicals used (bromine and chlorine fumes and hot mercury) were highly toxic; the images were difficult to view from certain angles.

The way in which the work of Niépce was moved forward by Daguerre was through accident and chance. According to Charles Robert Gibson, in The Romance of Modern Photography: Its Discovery & Achievements (1908), Daguerre discovered that iodine, made from seaweed at that time, was light sensitive by accidentally laying spoon on a iodine soaked plate. Indeed, Daguerre’s process rested upon previous experiments of Niépce who relied upon long exposures to be sure that the image had been indeed been captured on the pewter plated. But, as Daugerre found out, the image was already present, “latent,” and had only to be “developed” or coaxed into being. As Leggart noted, retelling a famous story of the accidental discovery of developing,

Louis Daguerre made an important discovery by accident. In 1835, he put an exposed plate in his chemical cupboard, and some days later found, to his surprise, that the latent image had developed. Daguerre eventually concluded that this was due to the presence of mercury vapour from a broken thermometer. This important discovery that a latent image could be developed made it possible to reduce the exposure time from some eight hours to thirty minutes.

According to Gibson, Daguerre exclaimed, “I have seized the light! I have arrested his flight! The sun himself in future shall draw my pictures!” The discovery of reliable and accurate record of reality captured faithfully and frozen in time astounded those who heard the announcement and saw the images. Knowing the long role of the camera obscura as a drawing aid, the famous juste milieu painter, Paul Delaroche, exclaimed, “From today painting is dead.” His excited utterance did not come true, but some of the earliest photographers came out of the studio of Delaroche. The American inventor of the telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse, met with Daguerre in March and went to the extreme of examining the details captured on the plates through a magnifying glass and said of scene, “Rembrandt perfected.” Tragically, even as the two inventors were meeting, the Diorama was burning down, taking with it Daguerre’s collection of daguerrotypes. Only twenty-five survive today.

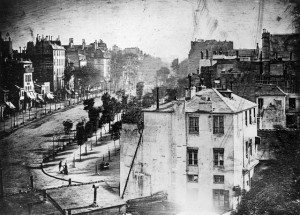

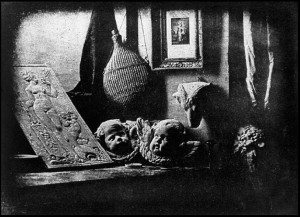

Of these surviving images perhaps among the best known was the ten minute exposure of the Boulevard du Temple (1838), where a man and a shoe shiner were willing to pose for that time. Due to the long exposure, all the other moving carriages and people were whisked away by the passing minutes, leaving only the stilled shoe-shining scene standing. Another well known image, Still Life with Casts or Still Life in Studio (1837) is a well arranged still life set up with clear artistic intent. The image contains a relief after Jean Goujon and is almost completely faded away as is the date itself. The canny self-promoting Daguerre sent daguerrotypes to King Ludwig of Bavaria, Emperor Ferdinand of Austria, the Czar Nicholas of Russia, the Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia, as well as other dedication plates to distinguished individuals. These gifts do not seem to have survived.

That said, the Daguerre still life is not the first still life photographed. According to Paul Martineau in Still Life in Photography (2010), that honor belongs to Niépce who captured the image of a well-laid table. The date of the photograph, which has been lost, is unknown, and the image that is known today was a photomechanical reproduction published in 1893.

Although the invention was taken up in Europe and America with alacrity and became enormously popular, Daguerre seems to have faded from the photographic scene he created and allowed the resulting mania for photography to carry on without him. Only one of his dioramas survives today and it was finally restored only in 2013. The restored eighteen by twenty foot diorama is located behind the altar, in front of the rotunda, of Saint Gervais-Saint Protais church in Bry-sur-Marne, the last stop of Daguerre before his quiet death after a secluded life. The painting provides an optical illusion that there is an entire church within the church itself. Daguerre’s last gift to France.

Restoring the Diorama

The Diorama during the day

The Diorama at night

Despite his subsequent decline in history, the name of Daguerre was inscribed on the Eiffel Tower when it was erected in 1889 to celebrate the centennial of the Revolution and the nation’s great inventors.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.