John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

The Unlikely War Artist, Part Two

Made towards the end of his career as an elite portrait painter to the elite families of America and Europe, the famous painting of a scene the artist actually witnessed, Gassed (1919) became one of John Singer Sargent’s most famous and often reproduced paintings. Sargent had a final and unexpected interlude as an artist during the Great War. Sargent made numerous studies for the painting which, in the end, was huge, measuring 7 and a half by 20 feet. Gassed was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1919 and was declared “The Painting of the Year,” and, despite its controversial reception has become one of the iconic works of the Great War. At the time its execution, the painting was intended to show the importance the sacrifice of a generation, cut down in its flower, as it were.

John Singer Sargent. Gassed (1919)

All the young men in Sargent’s painting were ideal icons of the English soldier, all bearing their wounds and pains with the forbearance of true aristocrats. It would be inevitable that Sargent, a portraitist of the famous and wealthy, would find a lingering classical beauty and order in a scene that, in real life, would have surely been one of fear and terror and uncertainty. The procession of beautiful young men proceeds melodiously across the vast canvas, attesting to the stoicism taught to them, probably, given the artist’s milieu, to their training in public school. Year later, one of the heroes of Operation Market Garden, Sir Brian Urquhart, described his schooling and its tradition of service:

“..almost across the whole British public school system, because the system, as such, was designed to staff a very large empire run by a small, off-shore island. I mean the idea was that unless you were some sort of kind of a genius, like a musician or a painter or a poet or something, you should concentrate on the idea of serving. And it wasn’t a priggish idea – it seems to be not a bad idea really – and I think we were very much brought up to think that unless we displayed some fantastic genius for something, we would be lucky to be in public service, or indeed earlier on, to go into the church – the Church after all is a state religion in England, unbelievably – or to go into the army, to come to that. These were the main sources of public service. I wanted to be a civilian. And, you know, I think it wasn’t a bad idea – although bad luck on all those people we were going to rule over in the colonies – so you trained a whole group of people who would do that, and, incidentally, who would go to some distant part of the world and stay there their whole working life.”

Sargent, who was familiar with the nineteenth century tradition of heroic military painting, found this modern war dishearteningly free of glory and it is notable that the artist painted a composition consisting of one color–the dun, mud color of the contemporary uniforms, designed to blend in with the bleak surrounding of the Western Front. For a public anxious to find nobility in a war of attrition and the long siege of the trenches, Gassed would have been deeply satisfying: beautiful and brave, classical without critique, a gesture towards the nobility of service and sacrifice. Winston Churchill whose dubious accomplishments up to that point included the slaughter at Gallipoli, noted the Sargent’s “brilliant genius and painful significance,” but he was throughly in favor of continuing the use of gas in future wars. As Marion Girard pointed out in her 2008 book, A Strange and Formidable Weapon: British Responses to World War I Poison Gas, “Churchill captured the sentiments of many of those who were enthusiastic about, not just tolerant, gas. He saw it as a useful weapon as well as a unique one whose reputation was unnecessary negative..he said it was ‘too silly’ not to use the weapon and that a any objections were ‘unreasonable.'” And yet the painting shows the full impact of one of the inescapable attacks of a remorseless vapor. The line of walking men pick they way between two rows of soldiers lying twisting in agony on the ground and, to the right, another line of marchers grope towards the same goal, the hospital tent. Although the effects of a gas attack could take twelve hours to materialize, the chances of survival were slim and, if one could recover, the effects of the gas were permanent.

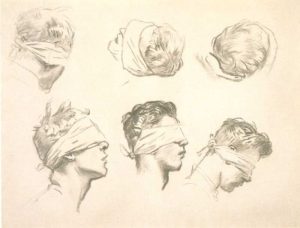

The intent of the painting, when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy, was clear to the contemporary viewers: its obvious references to classical art and its bid to be a modern history painting. The blinded soldiers, guiding and supporting one another, were also symbolic of the comradeship of the War, eliding the true and grotesque effects of the gas. In contrast to the true debilitating effect of gas, the young men retain their brave nobility. According the 1917 account of Arthur Hurst in Medical Diseases of the War:

The first effect of inhalation of chlorine is a burning pain in the throat and eyes, accompanied by a sensation of suffocation; pain, which may be severe, is felt in the chest, especially behind the sternum. Respiration becomes painful, rapid, and difficult ; coughing occurs, and the irritation of the eyes results in profuse lachrymation. Retching is common and may be followed by vomiting, which gives temporary relief. The lips and mouth are parched and the tongue is covered with a thick dry fur. Severe headache rapidly follows with a feeling of great weakness in the legs; if the patient gives way to this and lies down, he is likely to inhale still more chlorine, as the heavy gas is most concentrated near the ground. In severe poisoning unconsciousness follows; nothing more is known about the cases which prove fatal on the field within the first few hours of the “gassing,” except that the face assumes a pale greenish yellow colour. When a man lives long enough to be admitted into a clearing station, he is conscious, but restless; his face is violet red, and his ears and finger nails blue ; his expression strained and anxious as he gasps for breath; he tries to get relief by sitting up with his head thrown back, or he lies in an exhausted condition, sometimes on his side with his head over the edge of the stretcher in order to help the escape of fluid from the lungs. His skin is cold and his temperature subnormal; the pulse is full and rarely over 100. Respiration is jerky, shallow and rapid, the rate being often over 40 and sometimes even 80 a minute ; all the auxiliary muscles come into play, the chest being over-distended at the height of inspiration and, as in asthma, only slightly less distended in extreme expiration. Frequent and painful coughing occurs and some frothy sputum is brought up. The lungs are less resonant than normal, but not actually dull, and fine riles with occasional rhonchi and harsh but not bronchial breathing are heard, especially over the back and sides.

In the 2012 book, Painted Men in Britain, 1868-1918: Royal Academicians and Masculinities, Jongwoo Jeremy Kim described the way in which the sixty-two year old artist prepared himself to approach the Great War. “During the Great War, Sargent ‘refused to read’ any war poems except for Julian Grenfell’s ‘Into Battle.’ Sargent explained, “The verses are very fine and moving–there is something unusual in the sensation conveyed of all his perceptions and all his sympathies being keyed up to a high pitch by something enormous that is behind the scenes.'” This poem, published on the occasion of Grenfell’s death in 1915 at Ypres was far from heroic; it was a poem written by a soldier who obviously felt that he was doomed:

According to Kim,

“..categorically contradicting the gruesome medical facts of the chemical destruction Sargent’s painted youths would have experienced, the warm light in gold and the delicate air in the subtle pastels in Gassed invoke calm euphoria as thought to mock the jingoist slogan Dulce et decorum eat pro patria more (It is sweet and decorous to die for one’s country) and to reveal its utter absurdity. The perfumed atmosphere of easy contentment in Gassed is almost more jarring that the panic Wilfred Owen’s ironically titled poem indicates. The chromatic aberration in Gassed constructs an anguished irony,coloring the juxtaposition of the ideal of heroic death and its reality..”

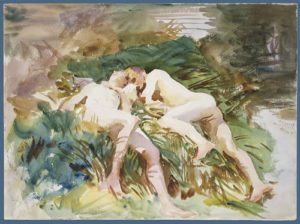

Kim continued in his critique of Gassed by comparing it to Sargent’s murals in the Boston Public Library, a project which had absorbed the artist for thirty years. He finished the murals in 1919, but the painting of the gassed victims was unsettlingly akin to the tangle of male bodies in his 1916 lunette panel Hell in the Library.

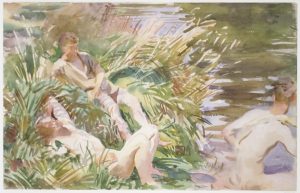

The author noted, “..Gassed adorns gruesome mass death, achieving the romantic chromatic allure in roes, lilac, and daffodil..in Gassed, the bodies of the young men wrapped in the romance of floral pastel shades betray fascination and desire. Every man in the panel is young, fit, and handsome in his uniform. Transformed into a grand spectacle, Tommies, like so many dandies, make endless layers of a sweet mille-feuille for the eye, lying down together feeling their fellows’ bodies against their own.” Kim notes the apparent class of the victims imagined by Sargent, remarking on their resemblance to earlier society painting which portrayed

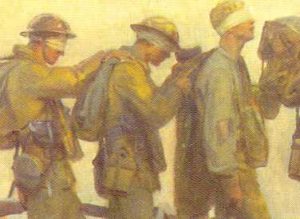

Sargent painted a number of studies of British “Tommies” at rest

“..supine affluent young people..the same gestures and postures, representing languorous pleasure in repose and luxury, are applied to groups of choking and vomiting men who are blinded, burned, blistered, and castrated by a chemical weapon. They lie on the ground no two enjoy the sun or the breeze. These men are recumbent because they are poisoned and because their death is intoxicating and nonbonding Neatly dressed, combed, and freshly youthful, the sensuality of Sargent’s Tommies is thus deeply discordant. Their collective horizontal incapacitation becomes a repose following an unimaginable orgy of destruction.”

These studies may have served as partial inspiration for Gassed

While the general public and the mainstream art audience were pleased by the restraint shown by Sargent, who congenitally could not, would not reveal the truth of chemical warfare to his audience, the avant-garde art world viewed the painting with scorn. Indeed the very popularity and immediate acceptance of the painting almost guaranteed the reaction of those who felt that representing the Great War should go beyond a social commentary on the beautiful deaths of the upper class men who expired so gracefully.

The Bloomsbury Group was merciless in its attacks on Gassed. E. M. Forster, the great English observer of upper class behavior and sexual repression, immediately decoded the message: “You were of godlike beauty–for the upper classes only allow the lower classes to appear in art on condition that they wash themselves and have classical features. These conditions you fulfilled. A line of golden-haired Apollos moved along a duckboard from left to right with bandages over their eyes..” Allen McLaurin in his book Virginia Woolf: The Echoes Enslaved added that Forster thought Gassed to be “unreal picture of war and is therefore immoral.” In his 2007 book on Forster, Achievement of E. M. Forster, John Beer noted that the author “pours bitter scorn on an Academy picture of the trenches which he finds hanging amid conventional paintings of ‘important people.'”

In other words, the painting was out of context, shown with society portraits, and was not in the destination for which it was intended, the never-built Hall of Remembrance. Today Gassed is in the Imperial War Museum, where it lives comfortably with other official painting of the War, including Paul Nash’s The Menin Road and Stanley Spencer’s Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916. But its initial showing at the Royal Academy in 1919 betrayed Sargent, revealing the origins of the painting. Forster immediately pounced, writing, “It was all a great war picture should be, and it was modern because it managed to tell a new short of lie. Many ladies and gentlemen fear that Romance is passing out of war with its sabres and the chargers. Sargent’s masterpiece reassures them. He shows that it is possible to suffer with a quiet grace under new conditions..” Foster imagines the adjacent paintings of social queens saying, “‘How touching,’ instead of ‘How obscene.'”

Virginia Woolf joined Forster in her condemnation of the painting. As usual, Woolf is indirect and elliptical in her complaint: “A large picture by Mr Sargent called Gassed at last pricked some nerve of protest, of perhaps of humanity. In order to emphasize his point that the soldiers wearing bandages around their eyes cannot see, and therefore claim our compassion, he makes one of them raise his leg to the level of his elbow in order to mount a step an inch or two above the ground. This little piece of over emphasis of the surgeon’s knife which is said to hurt more than the whole operation.” But, as McLaurin pointed out in 1973, the art critics did not always have the final word. If the question is not art but realism, then a letter from a field ambulance driver in The Athenaeum answered Woolf’s criticism by saying, “I saw Mr Sargent collecting his details. I have seen the picture in question, also, and it is the man at the end of the file that Mr Sargent has portrayed in this action. It is ‘over-emphasis,’ but on the part of the man–not that of the artist. Whether it be good art to depict this peculiarity I am not competent to say, but it is a depiction of the truth.” For one hundred years, this painting has been argued about, a fate that probably would have astonished the artist who was fulfilling a commission, which was his life long career. Gassed irks and irritates as it draws admiration because it sums up the myths and legends of the Great War. Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth mourns the loss of innocence and the scything down of her generation of beautiful young men. The poets and the poetry, the art and the artists, all come from the upper classes, an eloquent generation that rages against its fruitless gift of its greatest possessions, their lives. If Gassed carried any truth of message is the often told tale of how the finest flowers of the public schools dedicated themselves to service and selflessly gave their fates and futures over to a greedy and grateful nation. On one hand it romanticized a very unromantic War, but on the other hand, it remained England that an entire generation had been irrevocably lost, a lost that led a nation into years of “appeasement” to a mad man, a stance preferable to revisiting Gassed. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.