Samuel Borne: Kashmir and the Aesthetics of Conquest

In her seminal book, British Rule in India: A Historical Sketch (1857), Harriet Martineau called India “our great Asiatic dependency” and described the Himalayas as “a steep slope” like “a diversified wall with embrasures, covering an area of from 90 to 120 miles in breadth, and running a line of 1,500 miles. From a time beyond record the ridge of this slope has been called by the people who live below it is the Abode of Cold or of Snow–Himàlaya.” She continued to explain the meaning of the motion range to the British people, “..we need not scruple to mount the Abode of Cold–to the very palace of the old divinity–and use his standpoint, and borrow his eyes, for our survey of our own dominions lying below.” This is an elegant statement of Empire, clearly linking the divine right to rule borrowed by the English people from god with exploration which was in turn coupled to imperialism. Indeed, understanding the journeys of Samuel Bourne into the Himalayas it is necessary to understand The Great Game. The Himalayas are a long and majestic mountain range that runs the entire border of northern India. Most of the Himalayas lie along the border of China and India, but Bourne’s destination was a small portion of the mountains, a territory contingent to British controlled India, the independent (as of 1846) kingdom of Kashmir. Kashmir, lying north and just outside of direct British interests was interesting the the Empire because this part of the range erected a formidable barrier to invasion from Russia and was cut by trade routes that were vital to the interests of trade and commerce.

For the second half of the nineteenth century, the Empires of England and Russia fought a long and silent “cold war,”struggling for control of the various “stan” territories–Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan–that stood between them both. An examination of the modern maps, with all these territories clearly spelled out also explains the Crimean War (1853-1856) in which England and France joined forces with Turkey against Russia in order to prevent the Eastern Empire from threatening the Ottoman Empire along the Danube River. Russia was also threatening the British hold on India along the northern borders, thwarted only by the mountains and the buffer zone of territories such as Afghanistan, which both Empires attempted to control, a task that has historically proven to be impossible. In point of fact, the first English photographer to explore the Himalayas was James Burke who entered into the contested zone during the First Afghan War and the First and Second Sikh Wars, early skirmishes in the Great Game. In his 2002 book, From Kashmir to Kabul: The Photographs of Burke and Baker, 1860-1900, Omar Kahn referred to the “colonial imagination’s conquest of Kashmir.” What Kahn was describing was an emotional investment on the part of the British in what was essentially a fantasy that would be created by an English eye that sought both the familiar–forests, lakes, and villages–while also glorying in the majesty of mist-veiled peaks that ascended into the clouds while below two conquering giants engaged in feints towards one another in the valleys below.

The Great Game was a chess match between two burgeoning Empires, a game, which given the difficult territory, was a contest neither could win. For the British, Kashmir was a mysterious region at the edges of its official borders, a land of legend and myth. Today, Kashmir, a largely Muslim territory is described as “Indian-controlled,” a euphemism that elides the fact that Kashmir is divided between Pakistan and India and that the Indian “part” of Kashmir has been engaged in a decades long and bloody struggle to separate itself from the clutches of the massive continent. In the 1860s, politically, Kashmir was a buffer zone, in a time of imperialism, the Himalayas were places to be explored and conquered, mapped and tamed by the ever expanding British interests. When Bourne photographed the Memorial for the fallen at Cawnpore, the framing of the architectural homage to the fallen was an obligatory stop for any photographer of Empire, but his eyes were set on places less conquered and claimed by his predecessors. Like other photographers in India, Bourne was a professional, making all the steps and stops expected by the home audience identifying itself with the conquests of the British Empire, while seeking new scenes not so familiar. In his three excursions into Kashmir, from 1863-1869, Bourne left behind the urban areas of India and the culture he held in a certain amount of contempt and entered the realm of the sublime. In November of 1862 he wrote,

What a mighty unbarring of mountains! it was impossible to gaze on this tumultuous sea of mountains with being deeply affected with their terrible majesty and awful grandeur, without an elevation of the Sou’s capacities, and without a silent uplifting of the heart to Him who formed such stupendous works, whose eye alone has scanned the red depths of their sunless recesses, and whose presence only has rested on their mysterious and sublime elevations; and it must be to the credit of Photography that it teaches the mind to see the beauty and power of such scenes as these, and renders it more susceptible of their sweet and elevating impression.

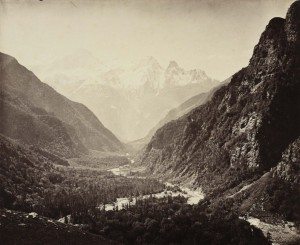

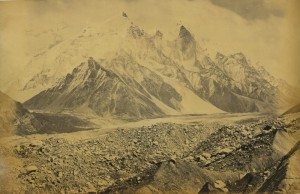

Wooded Valley from Fulaldarn with the Srikanta Peaks in the Distance (1860s)

The Kashmir beckoned Bourne, attracted by its relative inaccessibility and remoteness and the legends that still cling to the very name itself. The Himalayas must have seemed to Bourne to be amenable to the categories of British landscape painting, especially the “sublime.” Just as in the American West, the colonizing mindset would have framed the aesthetics of photographing the unknown in a way to make the strangeness seem both novel and familiar at the same time. In other words, during his three treks into the Himalayas, Bourne familiarized himself and his audience with the magnificant scenery of Kashmir while, as Sandeep Banerjee pointed out in his 2014 article “‘Not Altogether Unpicturesque’: Samuel Bourne and the Landscaping of the Victorian Himalaya,” the photographer tamed the sublime into the picturesque. But Bourne’s description of his own work, evokes his personal feelings of awe and wonder, evoking poetics, “What a mighty up bearing of mountains! What an endless vista go gigantic ranges and valleys, untold and unknown! Peak rose above peak, summit above summit, range above and beyond range, innumerable and boundless, until the mind refused to follow the eye in its attempt to comprehend the whole in one grand conception.”

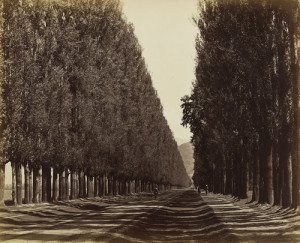

Samuel Bourne. Poplar Avenue. Srinagar. Kashmir (1864)

But Bourne also described his mission in India was to search for the “Indian picturesque.” He made three trips in to the Himalayan ranges, substituting what were “Photographic Expeditions” for imperial explorations. He first explored the Simla Hills and Sutlej valley in 1863, returning with one hundred forty seven photographs, and then he scouted the Kangra Valley and Kashmir in 1864, ending his time in Kashmir with a six month expedition to Kulu, Lahoul and Spiti in 1866, where he photographed the Gangotri Glacier, the source of the Ganges. The result was thousand of photographs and four series of letters he wrote for the British Journal of Photography, “letters” which were not published in their entireity until 1870. Bourne was very fortunate, according to all accounts, to have gone into partnership with Charles Shepherd, his co-photographer and printer. The result of their Calcutta business, Bourne & Shepherd, were beautifully developed exquisitely rendered flawlessly executed images made from wet plates. These photographs were seamless film capable of displaying extreme detail with a quality that made him the most successful photographer of Indian scenes and allowed him to expand his business to Bombay and Simla.

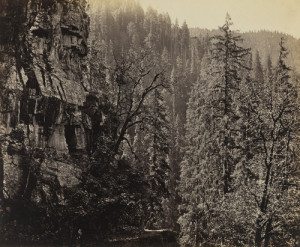

Samuel Bourne. View in Narkunda Forest, Chini Valley, Himalayas (1864)

Writing for the Getty Museum, Sarah McDonald’s article “Man of His Time,” described as epitomizing “all the clichés of the Victorian gentleman abroad: a conceit of his British standing; a bullying, colonial attitude towards the ‘natives,’ traveling with a ridiculous quantity of extraneous luggage including ad hoc pieces of furniture, and an almost lunatic persistence in pursuit of his hazardous expeditions.”

The quest into Kashmir for Bourne mirrored the next phase of exploration and discovery on the part of the ever-confident Britain. Now that relative calm had been imposed on the realm, such ventures now fell into the realm of extreme sport. Women were able to participate in such adventures but the individual conquest of exotic locales were mainly a male enterprise that, in the minds of imperialists, was linked to pig-sticking and polo, quintessentially masculine pastimes. Exploring the far off mountain ranges involved the Englishman in the role of conquerer and leader, employing scores of servants–Bourne employed forty some on his first journey (and they quit his service and abandoned him in dangerous circumstances)–and gave him the sense of being an individual ruler of his own enterprise. Samuel Bourne. Gangotri Glacier and the Bhagirathi Peaks (1866) As Pramod K. Nayar, the great post-colonialist scholar of the University of Hyderabad, pointed out in English Writing and India, 1600–1920: Colonizing Aesthetics (2007), exploration was linked to hunting and domination and to masculinity and Bourne would have been transporting his heavy cameras and multiple glass plates in a fairly domesticated adventure. Writing in what Naya described as “a discourse of colonial conquest,” Bourne complained that even his large size cameras could not encompass the scope and expanse of the Himalayas. Naya continued in his explanation of the meaning of concepts, such as an “aesthetic mode.” It is in this context of a disappearing exotic, excessive tourism, the sense of vulnerability and the desire to react colonial control (after 1857) that the picturesque is revived in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The search for picturesque scenes in an era of greater imperial control, mapped terrain and improved transport facilities scaled for and resulted in a new version of the aesthetic..Danger is as integral to the luxuriant as the passive to the beautiful. What the English traveller seeks is an escape form a routine of everyday life and therefore embarks on a quest for difficulty. And Bourne’s explorations were as extreme as his ego, but he earned his reputation as being a peerless and fearless photographer. In addition to carrying a food supply of live sheep and goats and a portable darkroom tent, he photographed at a record height of almost 19,000 feet where he achieved the promise of photography, its “marvelous truth and power” and its ability to record and render, all in the spirit of colonial power. The military-like marches by Bourne could not have been carried out without his scores of Indian subalterns, who rarely if ever were depicted in his scenes of photographic conquest, termed by Nigel Leask as “imperial picturesque” in his 2004 book Curiosity and the Aesthetics of Travel-Writing, 1770-1840. The Kashmir of Samuel Bourne is “orientalized” in the sense that the region is fashioned into The Other or the alien yet familiarized but wild Indian version of the Highlands and the Lake Country. The mere use of the words, “picturesque”and “sublime” in the context of “colonial” and “imperial” describe the enterprise of Empire in India which used an imperial discourse, both text and image based, which settled upon the continent like a heavy hand. The British armchair traveller was given the illusion of power and containment over India, even in its most dangerous and remote regions, and these adventurous wanderings of the photographer proved that these distant lands of English desire could be owned and set in place as the “jewel in the crown” in the regalia of Queen Victoria. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.