THE CAMERA AND THE WAR

Matthew Brady’s Operatives

“My greatest aim has been to advance the art of photography and to make it what I think I have, a great and truthful medium of history.” Matthew Brady

Without a doubt the best book written on the Civil War is by Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (2008). While other books discuss the rise and fall of slavery or the major battles or the heroic biographies of the leading actors, this book discusses death and the toll of the war on both sides: the destruction of lives and families and the enormous cost paid to keep the nation intact. If anything separated the American Civil war from preceding wars it was the sheer scope of the dead and wounded in this the first modern industrial war after the Crimean War. The cause of this high casualty rate was the same as it would be in the Great War, the clash between eighteenth century battle strategy and nineteenth century military technology, which simply mowed down fields of young men. In 2012 the established count for the dead on both sides, 618,222, was updated, using modern statistical methods by J. David Hacker, a specialist in demographics who combined his expertise as a historian at Binghamton University in New York State, who came up with a new figure of 750,000. Hacker indicated that the number was approximate and that his studies suggested a span between 650,000 and 850,000. The article “New Estimate Raises Civil War Death Toll” by Guy Gugliotta in The New York Times quoted historian Eric Foner at Columbia University:

It even further elevates the significance of the Civil War and makes a dramatic statement about how the war is a central moment in American history. It helps you understand, particularly in the South with a much smaller population, what a devastating experience this was.

This defining event changed America’s understanding of itself as a nation of laws that would not tolerate a lawless and immoral society within its borders. The argument over the extent to which the states of the union had “rights” ended with the Civil War–no one had the right to violate the Constitution and the rights of other human beings to be free. But this understanding won by the War was long and late in coming. For those involved in the conflict, the reasons for fighting and dying altered over the years with the political landscape, but for the photographers who, acting as photo journalists, “covering” the war, the question was not the cause of the war but the effects of the war. The photographers on the scene during the four years, 1861-1865, had an assignment considerably different from that of Roger Fenton (1819-189) in the Crimea. Fenton was supported by well-placed patrons and worked under the watchful eyes of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. His task or brief was to find out what was really going on but his unspoken instructions were to not depict the war in a graphic manner. The Civil War photographers were engaged in what was a combination of journalism and business and documentation. The intent was to inform the readers of various publications through engravings of the photographs and to sell the separate images to the interested public.

Matthew Brady

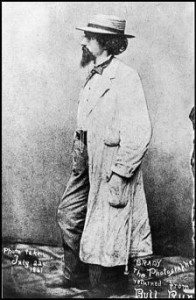

The prime supporter or organizer of the photographic survey of the Civil War was Matthew Brady (1822-1896), a well-established New York photographer whose studio and place of business was already famous at the time the war broke out. One of the pioneers in portraiture, Brady had opened the Daguerrean Miniature Gallery in New York as early as 1844. So great was his success he was able to open a second establishment in Washington D. C. in 1848, but, because it was undercapitalized, it closed a year later. It should be noted the Brady had poor eyesight and did not do the actual photographing himself. Instead he took care of the staging and posing of the men and women who flocked to his studio. In 1850 he published a book of lithographs, based on the extensive collection of Daguerreotype portraits Brady had taken of famous Americans, Gallery of Illustrious Americans. Sadly, the series of albums were expensive and the public interest was low and the publication, despite critical praise, was discontinued.

The following year, 1851, he went to London for the Great Exhibition, where he showed a large sample of his work and won a bronze medal for his portraits. Of equal importance to his visit was the fact that he met a Scottish photographer Alexander Gardner (1821-1882), who was already involved in the new process of collodion–photography using the negative-posivite method. Understanding that this method was the future of photography, Brady learned the process himself and later convinced Gardner to reestablish himself in America and run a new studio in Washington D. C. in 1858. It is not clear precisely why Matthew Brady decided to photograph the Civil War when the nation split in two in 1861, but it can be assumed that he, like so many others, thought that the war would be a short one. The familiar phrase “home by Christmas” was not the be the case and, during the next four years, Matthew Brady would become responsible for collecting and distributing a massive archive of imagery, chronicling a long and bloody war. As one of the lead “operatives,” Alexander Gardner was well-placed, near the front lines, to follow the conflict and thus was a major actor in following the campaigns.

According to photo historian Kevin McElroy,

Brady was a dandy who wore doe-skin pants and thick glasses; he didn’t make his own photos. He hired operators..Gardner was the brains behind the operation.

Unlike Roger Fenton who had had to travel a long distance go get to the Crimea, Brady’s team of photographers found the war on home ground, often only a few miles away. The war Fenton witnessed was a siege war, a static war, but the American Civil War was a mobile one, pushed up and down the east coast by railroads. On one hand the Southern troops, rather than simply waiting for an assault from the North and defending their territory, chose to thrust and parry their way into the Union, pouring over the border and into the Federal territory. Once the Southern advances had been broken and the Confederate Army in the east was weakened, the Northern armies were able to move south, fighting many small battles along the way as they moved mercilessly and remorselessly from north to south. Although the Confederate Army never got any further into Union territory than Pennsylvania, the Union army penetrated deep into southern territories, marching, as was said, all the way to Georgia. Unlike Fenton who was embedded with that British forces, Brady’s operatives were on their own and the main photographer to follow General Sherman into the South was George N. Bernard (1819-1902), who literally could not keep up with the speed of the advance and photographed the ruins left in the wake of “Sherman’s March to the Sea.”

Barnard recorded the ruthless “total war” waged on the population of the South in order to destroy its infrastructure and break its will and destroy its ability to wage war. Sherman blew up the railroad tracks and the train full of ordnance belonging to the Confederate General Hood in Atlanta in 1864, setting off a conflagration that consumed the city.

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina, the city where the first shot was fired at Fort Sumpter in 1861, photographed four years later by Bernard.

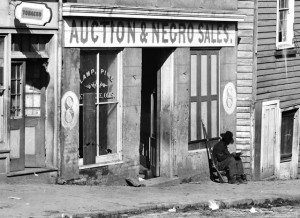

It was not until after the Union victory at Antietam that President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) felt confident enough to issue the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, stating that all slaves in the slave states “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Barnard captured a common sight in the slave holding south, an auction house, as he and the Union Army marched South. Because many of the photographs of the Civil War were issued under Matthew Brady’s name, it has been difficult to give proper credit to individual photographers. In fact, Alexander Gardner split with Matthew Brady two years into the war over the issue of appropriate attribution and set off to finish the war on his own. It is possible to credit Bernard with his own work because he had split off from those who worked on the battle sites near the border. The Metropolitan Museum of Art listed many other lesser known photographers who continued to work under Brady, including William R. Pyell, J. B. Gibson, George Cook, David Knox, D. B. Woodbury, J. Reekie and Stanley Morrow.

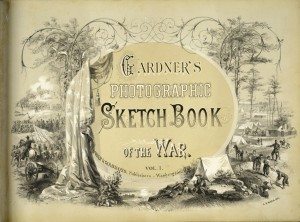

After the war was over, Gardner published his own portfolio of Civil War photographs, under the title Gardner’s Sketch Book of the War in two volumes, and, he published the work of the other major photographer on the scene, another immigrant, the young Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882), from Ireland, under his own name. In point of fact, Gardner had taken O’Sullivan and another photographer, James F. Gibson, with him when he split from Brady and he and O’Sullivan produced some of the most powerful and memorable images of the terrible war, catching its horrors without flinching as they gazed through the lens of their cameras.

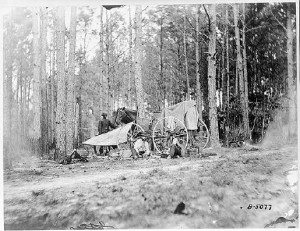

The technology of collodion had not advanced much over the past decade since Fenton drove his photographic van across the plains of Balaclava, and these photographers had vans were also filled with glass plates, chemicals, and developing equipment. These vans, such as the one stationed at Petersburg, Virginia, seen below, stayed at a safe distance from the fighting to protect their contents, while the photographers moved toward the front lines or the battlefields only when it was safe to do so.

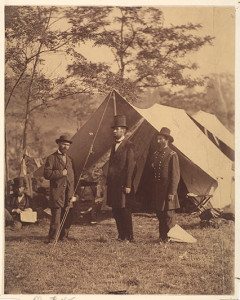

Like Fenton, they could not capture action and had to rely upon live subjects to pose for them, and, again like Fenton, they took portraits and organized small vignettes of life in camp. One of the more interesting portraits is attributed to Alexander Gardner and shows the President towering over both his bodyguard, Allan Pinkerton, on the left and Major General John A. McClernand on the right. Taken at the Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, on October 4, 1862, the triple portrait is fascinating because of the un-artful way in which the tent pole seems to emerge from Lincoln’s top hat, the piece of paper that has apparently flown against McClernand’s leg and the odd man in the back, holding up a white sign. One wonders why Gardner did not remove the paper on the ground or ask Lincoln to move to the right.

The most famous images were those of the dead. As difficult as it is for us to understand today, these images of the war would be displayed in Matthew Brady’s studios in New York and Washington and were later published in Gardner’s Sketchbook. The first exhibition–yes, that is the correct word–of death took place in Brady’s studio in New York in 1862, in a show entitled “The Dead of Antietam.” As The New York Times wrote in response in October, “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it..”According to Faust, the newspapers of the time would not reproduce photographs of the dead, just as they are reluctant to do so today.

The dead at Antietam photographed here by Alexander Gardner were Confederates caught in a crossfire on the road to Hagerstown. The name of the road, Sunken Road, was changed to “Bloody Lane” after the battle. A journalist reported on the same scene:

Of the enemy’s wounded we cannot judge, as the most have been taken away. His dead certainly outnumber ours. Between the fences of a road today, in a space of 100 yards long, I counted more than 200 Rebel dead, lying where they fell. Over acres and acres they are strewn, singly, in groups, and sometimes in masses, piled up almost like cordwood.

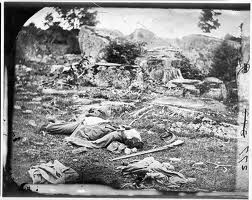

Bodies of Confederate artillerymen near Dunker church photographed by Gardner in the aftermath of September 17, 1862, when more than 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded at Antietam Creek

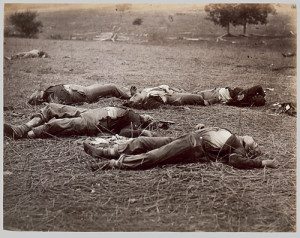

Devil’s Den After Gettysburg titled “Son’s of the South” by Gardner

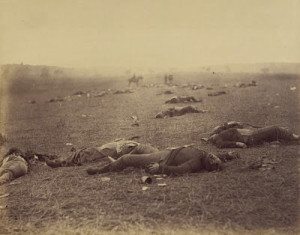

The famous “Harvest of Death” photographed by Timothy O’Sullivan was cropped later by Gardner who printed the image as an albumen print off of a glass negative. The severe cropping makes it difficult to locate the actual site on the battlefield of Gettysburg. Apparently for the photographers, the where is of less interest that the what and the message the image conveyed. Gardner’s caption for the Sketch Book read in part:

Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

The extent to which those images of death were unprecedented to the public eye must be stressed. There were simply no precedents for such a level of stark realism. Some of the photographs were stereographs, meant to be looked at through the two lenses of the stereo viewer for a three-dimensional image, for an intimate, up close and personal experience of death and its aftermath. The bleached out black and white sight of a corpse would have been a shock to any viewer. To the extent that the public had image of war, they were based on military paintings, which portrayed the heroism, valor, color, excitement of war and all its magnificent uniforms, splendid horses and dashing young men. Especially in the South, the Civil War was imagined by all those who participated to be a romantic adventure of gallantry, and it was in the South where the stark reality of modern war was displayed.

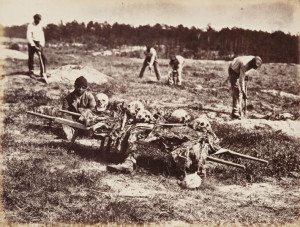

Unlike the northern territories which were largely spared, the South became an extended battleground from Pennsylvania in the north to Mississippi in the southwest. As Faust pointed out, up to that point in time, there was no policy or practice of organizing the obvious–the collection and disposal of the dead, which were everywhere, scattered about. Some of the most powerful images of the period are of the burials and reburials. The sights witnessed by the inhabitants of the embattled regions must have been traumatic, for it was the citizens who, for years, had to take informal responsibility for gathering and burying bodies and informing kin across the lines of their loved one’s death. This gruesome work of removing the dead from the battlefield for shipment home or to the new Arlington cemetery often fell to African-Americans as seen below.

Burial Detail at Cold Harbor, Virginia (1865)

Because Matthew Brady fell on hard times after he war, he was forced to sell his entire collection to the United States government in 1875 for a mere $25,000. The collection fell into safe hands and, for many years, into oblivion. The New York Historical Society showed the photographs taken by Matthew Brady’s operatives in 1866. Although the war had been over only a year, the public was eager to put the memories behind and while the photographs were understood to be a valuable record, they were a record of what people wanted to forget. The New York Times wrote March 30, 1866 that, “The faithful camera..has written the true history of the war..It is not merely what these representations are to us, but what they will be to those who come after us.”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.