THE DAGUERROTYPE AND PORTRAITURE

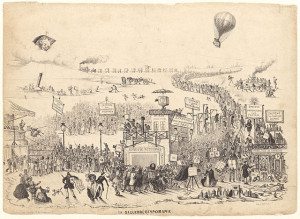

Daguerreotypomania

“Readiness” for Photography, Part Two

In 1989 the French photographer, Gisèle Freund wrote Photography and Society in which she attempted to explain the role of photography in mid-nineteenth century France. If one follows her thesis, it is no accident that the most extensive use of photography was for portraiture and no method of photography could produce more accurate images of the human being than the Daguerreotype. Invented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) after years of experimenting, the new process of capturing the likeness of nature was given to the public free of charge or patents. However, in comparison to the prevailing horizon of expectations for portraits, honed by paintings, silhouettes and miniatures and sketches, the face on the silvered plate was shockingly realistic in its unalloyed detail. In an age when mirrors were not as well manufactured as they are today and one saw one’s own image rather darkly and obscurely, the literalness of the Daguerrotype must have been a shock. But in an age before vanity would become a preoccupation, the public ignored its inherent unattractiveness (to today’s eyes) and rushed to have their pictures taken. Almost immediately photographic portraiture became embedded in European and American cultures, obviously fulfilling some kind of perceived need that must have pre-existed the release of the secret of the Daguerreotype and its process in August of 1839. A “mania” for the Daguerreotypes ensued.

Theodore Maurisset cartoon. French, Paris, December 1839

According to Freund, this “readiness” for photography can be located in the new composition of society in France itself. As was discussed in earlier posts on this website, there was a long period of technological preparing for photography and a time of scientific “readiness” for the technology was established out of the science communities. However, the next step had to be the establishment of an actual social use for photography and the first cultural inclinations seemed to have been to use the camera as an instrument of recording and documenting society itself. Freud pointed to the rise of the middle class and its need for self-fashioning or self-presentation as part of a social assertion of itself as being newly powerful and important. It should be noted in passing that this “middle class” was a localized city-based or urban phenomenon in France, which was in fact largely rural throughout the nineteenth century. This middle class was still small and located mostly in large municipalities and mainly in Paris, so it needs to be understood that the “mania” for portraiture would have been based in urban settings. In addition, although Freund referred to the photographic “industry,” it was the kind of industry that appealed to the French: it was small-scale, hand-made, not factory based, personal and depended upon exchanges between individuals. Photography, industrial or not, fitted well into the French tradition of luxury goods that had been the foundation of its economy for centuries as an object of consumption. This infallible method of recording the individual human also suited the needs of the middle class to establish a new method of portraiture that they could make uniquely its own.

Freund pointed out that it was the purchase of Daugerre’s invention by French government was a necessary step in making the invention available for everyone. French businesses were small scale and geared to local neighborhoods, and although photography was a rare mechanical device that could be potentially used in a variety of ways by the public, it was also easily adaptable by businesses. And so in the entrepreneurial spirit of the age and in the interests of the presumed “liberal democracy” of the July Monarchy, the government made photography a gift to the public. Freund pointed out that this “gift” was a slow, clumsy, expensive and complicated one:

Daguerre’s invention, moreover, was very inconvenient. First of all, the light sensitive silver plate could be used only after its exposure to dangerous idoized vapors. In addition, the plate could nobly be prepared just before use and had to be developed immediately after exposure. Finally, exposure time was often more than half an hour..the daguerreotype had yet another basic disadvantage: the process resulted in only one plate, and copies could not be made. Built by Daguerre himself and sold by the Paris optician Giroux, the first cameras were large and cumbersome, weighing 50 kilograms (over 100 pounds), including accessories. The price, no less imposing, varied between 300 and 400 francs, a sum very few could afford.

From these primitive beginnings, advances were quickly made: camera weight dropped or lessened and cameras became more lightweight, the quality of lenses were improved, the cost of both cameras and the plates lowered very quickly. The technology, perhaps because of its primitiveness, was well within reach of anyone who wished to use it and excellent manuals were written and printed for instruction. Once one had mastered the basic chemistry of the easily acquired chemical solutions, a person could go into business and take advantage of the social “readiness” for photography and fulfill the desire of the middle class to have its picture taken. Not only could anyone be a photographer, anyone could have his or her image captured for posterity. Suddenly, with the price within the range of the average person, one could see what one really looked like and one’s face could be preserved even after death, all for the cost of a few dollars. However, the exposure times were impossibly long: a full size silver plate took a half hour to complete the exposure, thirty minutes of unmoving torture. When the time was shortened, this improvement in the experience of being photographed was made, not in Paris, but in New York.

The American advocate for the Daguerreotype was the artist and inventor of the telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1892), who just happened to be in Paris by 1838 attempting to sell the French Académie des Sciences. In fact, as Sarah Catherine Gillespie pointed out in her book Samuel F. B. Morse and the Daguerreotype: Art and Science in America (2006), none other than François Arago who demonstrated his little-understood but potentially revolutionary device to send messages. It was during his stay in Paris that Morse made the acquaintance of Daguerre and met with the artist twice. He viewed some daguerreotypes in Daguerre’s office for the Diorama, located just down the rue de Marais. But it was during the next visit, this time to Daguerre’s rooms on rue de Neuve des Mathurins, when they were viewing some of the plates, that the photographer’s Diorama, burned to the ground, destroying the bulk of his life’s work.

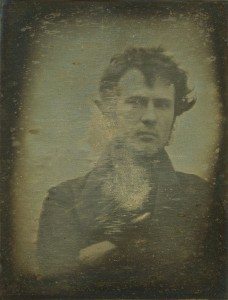

In March, Morse headed home to America, bearing with him a precise eye-witness account of the new phenomenon of the Daguerreotype and published an account of the process in a New York, New Orleans, and Philadelphia newspapers in April. Morse then worked with Dr. John Draper, a chemist, and Alexander Wolcott, who had a partner John Johnson, with whom he had made a camera. With the combination of better chemistry and a better camera, they set up in the glass house on the top of New York University and took the first daguerreotype portrait of Johnson. Sadly, the image, which was tiny, was lost. An earlier portrait exists, taken by Talbot of his wife Constance, but that was, of course, on paper. However, in the same month, October, barely two months after the announcement of Daguerre’s method in Paris, Robert Cornelius (1809-1893) in Philadelphia took a portrait of himself. Cornelius was a lamp maker and was part of the transition from whale oil to gas lamps, a business that was far more promising in the long run than photography. But he was interested in chemistry and managed to reduce the exposure time to five minutes, succeeding in standing still, eyes open in front of his office for five minutes. This slightly disheveled image was taken out of doors to take advantage of the needed light and Cornelius posed himself in front of a simple box, fitted with a makeshift lens lifted out of an opera glass. It is not recorded what the passers-by thought of the man who stood for five minutes without blinking.

Cornelius was a photographer for only two years but the work of attempting to take portraits with the Daguerreotype process was carried on in New York by Wolcott and Johnson, who discovered that lenses, as currently constituted, did not let in enough light and removed the lens altogether and utilized a mirror for light. The pair opened a studio in 1840 and began making small portraits for those willing to sit motionless for a long period of time, a physical stress that one victim described as “anguish.” The “mania” for Daguerreotypes as an idea was one thing, but developing the “industry” to make pictures on demand took the combined efforts of many people working together and separately, sharing their knowledge. New photographer Richard Beard opened a studio in London in 1841, utilizing the experiments of Daguerre, Johnson and Wolcott. In Paris Louis-August Bisson follow suit in the same year, offering portraits to the Parisians. The combined research and experimentation and the willingness of entrepreneurs to try a new business and the bravery of their uncomfortable subjects led to the improvement of technology, which allowed the Daguerreotypes to corner the market in public portraiture by the 1850s, the era of the Second Empire. Janet E. Buerger reported in her book, French Daguerreotypes (1989), that twenty-one million plates were manufactured in one year, 1851, alone. Beaumont Newhall, in The Daguerreotype in America (1976), counted that in Massachusetts 403, 626 daguerreotypes were made in 1855 and that in the United States there were 3, 154 photographers.

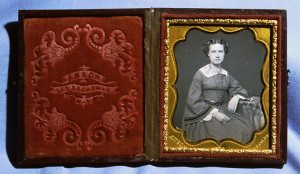

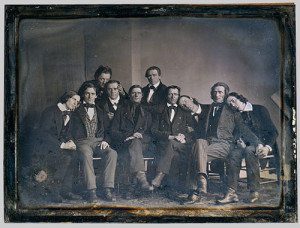

Although the people who took the daguerreotypes went in and out of the precarious business, one could have a portrait made in any big city on the East Coast of America and in Europe. The visit to a photographer was an ordeal. The exposure time was shortened, eliminating the need for a head brace, but the customer needed to be seated in full light and had to stare fixedly for a minute or so at the camera lens. No one could smile under such circumstances, giving the photographs of our ancestors a uniformly dour look. The sitter would receive a portrait of him or herself, dressed in Sunday best, sober faced, in reverse. The mirrored image had to be properly tilted to view and the gold washed surface was too sensitive to be touched or handled roughly. A veritable cottage industry sprang up to take care of the fragile silvered plates, which were protected behind a mat, a layer of glass, all taped together around the edges, and, by 1847, a brass frame, called a “preserver” was added to the assemblage. The entire package was when slipped into a silk lined wooden case covered in leather. By the late 1850s a thermoplastic protective case, which closed like a book, was preferred by the clients and the preservers of the images became more elaborately decorated, and the mats became smoother and thinner.

The subject presented him or herself to the photographer as a particular persona, a social construction that was deliberate and self-conscious. As Freund suggested, the millions of daguerreotypes capture not only fleeting instance in the time of an individual’s life but also a passage in social time, when the middle class was creating itself. Aping the upper classes, who had always had their portraits made in their palatial homes with a view to their grounds, signifying the trappings and the source of their wealth and noting their status, the middle class asserted its own claims to social prestige. Not only did one arrive at the photographer’s studio dressed in best clothes, s/he could also take advantage of an array of props in the atelier, from draperies to columns to elegant chairs, and a variety of accouterments, such as books and other decorative components. The illusion created was that one was “at home,” surrounded by signifiers. Often the sitter was joined by a spouse or a child, even very patient dogs, all conveying a social setting or cultural condition. Through baby pictures to wedding portraits to the final image taken after death, an entire life could be recorded and preserved for family and friends and descendants. There was of course nothing “real” or candid about these images. These pictures say much about social conventions of the period, the belief system and the values of the time. Defying reality in their artful construction, these first portraits capture a new breed of new people, city dwellers for the most part, business people more than likely, solidly middle class, ordinary and yet extraordinary, leaving behind a map of “mania” and a memory of the nineteenth century.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.