John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

The Unlikely War Artist, Part One

John Singer Sargent had the singular honor of being the official portraitist for the Gilded Age in America Europe, painting the last decades of a slightly decadent and negligent peace before the fabric of alliances, both family and political, unraveled. Perhaps it was only right and proper that the dashing artist should be among those who were asked to paint its tragic end. If his first great paintings had included an exquisite woman in a svelte black dress, then his last notable works would show the ruin and destruction of the young men, who were supposed to carry on that traditional way of life.

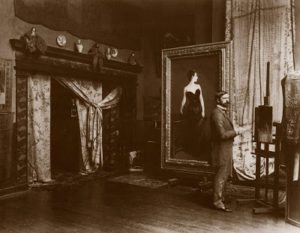

John Singer Sargent in his Studio with the Portrait of Madame X (1884)

Ironically it was also the task of this artist to depict the men who ordered them to die. The Great War was an unexpected climax to a glittering career unmarked by tragedy, but the life of Sargent, like that of everyone who lived through the War, could not go unmarked. It was the society painter, renowned for flash and dash, who would paint one of the great and moving images of what would be the First World War, and, in the process, would render one of the last history paintings of the nineteenth century. But over time, we have lost its original meaning.

John Singer Sargent. Gassed (1919)

In June 28, 1914 an obscure Serbian teenager, Gavrila Princip, assassinated the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Ferdinand. While the killing was the unexpected result of a nationalist plot gone badly wrong, the event proved to be the arbitrary last straw that caused the collapse of an uneasy calm before what would become a great storm. The Great War was the first modern war, but the British government was ready to control the cloud of information that would inevitably gather. Although it had been decades since the Crimean War in the middle of the nineteenth century, the government had learned hard lessons about the modern press and its power. Writing for The Times of London, the first “war correspondent,” William Howard Russell (1820-1907) was unflagging in his determination to report the truth of a war that was going very badly. Russell was a combination of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in an age before governments had come to understand the power of a war correspondent corresponding with the British people. In his dispatches from the Crimean front, Russell explained, in terms both intimate and overblown, a war that husbands, sons, brothers, and fathers were fighting. As Martin Bell wrote in 2009, introducing his book, Despatches From The Crimea, “During the Crimean War,it was due to Russell’s dispatches from the scene more than to any other single factor that the British government’s mishandling of affairs, and the gross negligence of the War Office in particular, came to light and that the resignation of Lord Aberdeen’s cabinet was brought about.”

Undoubtedly wary of another out of control Russell embedded with the military, un-beholden to anyone but an independent newspaper, the British government immediately established the frankly named British War Propaganda Bureau, with the sole aim of shaping the information that was to be disseminated not only to the British public but also to the rest of the world. Located at Wellington House, hiding behind a fictitious National Insurance Department, this top secret agency was completely unknown to the public until 1935. The secrecy was extraordinary when one considers that the government corralled prominent English writers and major publishing houses so that the appropriate point of view would be extolled. The list of authors reads like a who’s who of turn of the century literature, including Arthur Conan Doyle, Ford Madox Ford, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, and H. G. Wells. Overseeing all and controlling all was Charles Masterman. Masterman, perhaps remembering the telling images made by Matthew Brady and his photographers during the American Civil War, made sure that only two war official photographers were allowed to go to the front. Most of the photographs of this war were taken by the soldiers themselves.

The organization seemed to grow as the War continued and generated further operations. In 1916, the Propaganda Bureau became the Department of Information, with Masterman, as Director of Publications, being in charge of war paintings. Under Lord Beaverbrook, a British War Memorial Committee, which sent a group of prominent English artists to France, was established in 1918. The Committee gathered together mirrored the roster of authors supporting the official government perspective on the War: Augustus John, John Nash, Henry Tonks, Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, William Roberts, WyndhamLewis, Stanley Spencer, David Bomberg and other lesser known names. To be an “official” British war artist, during the Great War, meant to be under government control. The very nature of the job, which was to depict the war, carried within it a contradiction in terms, for communication and censorship do not rest easily with one another. More than a few of these artists had served on the Front themselves and returned as observers who could, like Paul Nash, measure the continuing damage of a long war on the land and upon human beings. Like Christopher Nevinson, many were censored and came under fire for their frank depictions of the dead or dying, but becoming “official” afforded an avenue for expression and an outlet for their outrage.

Out of place with this group of largely young men, John Singer Sargent came late to the party. Sent on a mission but the British War Memorials Committeee, he seemed to have had some difficulty deciding what to wear to the Western Front, but, like William Orpen, he was seconded to the headquarters of Field Marshal Douglas Haig. Sargent found this modern war unsettlingly unpicturesque. His remarks indicate that he was expecting scenes inspired by Lady Elizabeth Butler. Sargent noted, “The further forward one goes’, he wrote ‘the more scattered and meagre everything is. The nearer to danger, the fewer and more hidden the men – the more dramatic the situation the more it becomes and empty landscape. The Ministry of Information expects an epic – and how can one do an epic without masses of men?” Even more mundane was his brief: as an American expatriate, depict a joint operation of the Americans and the English. In the summer of 1918, the American Expeditionary Force had been in action only since May, fighting the prelude to the Second Battle of the Marne that would begin in July. Having learned of the way in which the British high command expended young lives with careless abandon, the leader of the American forces, General John Pershing refused to put Americans under European command, making Sargent’s commission difficult.

Gassed on Display at the Imperial War room at the Crystal Palace (1920)

The solution for the frustrated artist was to produce an enormous painting showing a suffering that was universal, the effects of a gas attack. The painting, Le Bac-du-Sud, Doullens Road, Doullens, Somme, France, would be called, simply, Gassed, and it would be completed in 1919. Being gassed had become by the end of the war a metaphor for all the mechanized savagery of the inhuman and inhumane war. By time Sargent was in France, the original gas, chlorine, which was carried in a terrifying green cloud, had been replaced by phosgene, a much slower killer. In analyzing the various gases used in the Great War, Marek Pruszewicz, writing for the BBC News, explained, “The most widely used, mustard gas, could kill by blistering the lungs and throat if inhaled in large quantities. Its effect on masked soldiers, however, was to produce terrible blisters all over the body as it soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed – not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.” It seems that the aftermath of a gas attack, witnessed and painted by Sargent, was the work of mustard gas (Yperite). The terror of gas was its slow, silent, creeping nature, its all encompassing cloud-like arrival, its all invasive properties made it a weapon more hated and feared than the other technological advances made during the War.

The actual event seen by Sargent was described later by Henry Tonks in a letter to Alfred Yockney on 19 March 1920: “After tea we heard that on the Doullens Road at the Corps dressing station at le Bac-du-sud there were a good many gassed cases, so we went there. The dressing station was situated on the road and consisted of a number of huts and a few tents. Gassed cases kept coming in, lead along in parties of about six just as Sargent has depicted them, by an orderly. They sat or lay down on the grass, there must have been several hundred, evidently suffering a great deal, chiefly I fancy from their eyes which were covered up by a piece of lint… Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes.” It is possible that the aftermath of a gas attack was as orderly as Sargent illustrated it, borrowing the classical frieze composition seen in Greco-Roman art. Disorder is kept to a minimum in the horizontal composition. Sargent undoubtedly knew of Antoine-Jean Gros’s painting of Napoleon on the Battlefield at Eylau, February 9, 1807 (1808), where the prone bodies at the bottom of the canvas form a foundation for the horizontal layers of the middle ground. As in the large painting by Gros, Sargent shows glimpses of scenes in the distance, spotted between the marching legs of the stricken soldiers. It is possible to glimpse a scene of a carefree football game, suggesting that war is a game, indicating that life will continue, or possibly alluding to the famous soccer matches played during the Christmas truce of 1914.

Modern eyes, accustomed to the absolute ban on chemical weapons see Sargent’a massive painting as horrific and painful, a statement about the barbarity of war, but the contemporary audiences were not supposed to cringe but to respond to the patriotism and classical pathos of the scene. Pruszewicz made the point in his article that, according to Richard Slocombe, Senior Curator of Art at the Imperial War Museum, the meaning was less about suffering and more about the spiritual mission of the War: “The painting was meant to convey a message that the war had been worth it and had led to a better tomorrow, a greater cause, that it had not been a terrible waste of life. It is a painting imbued with symbolism. The temporary blindness was a metaphor, a semi-religious purgatory for British youth on the way to resurrection. You can see the guy-ropes of a field hospital tent depicted, and the men are being led towards it.” Vera Brittain, who had lost her lover, her brother, and her innocence to the War, complained of the government mandated attitudes that this was a “holy war.” Of the victims of a gas attack, she wrote to her mother that she wished the English public could see, “We have heaps of gassed cases at present who came in a day or two ago: there were 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case–to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages–could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes – sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently – all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke.”

But, as shall be seen in the subsequent post, John Singer Sargent had no intention of showing the horror of modern war nor was his painting about the actual suffering of the real victims of an attack of mustard gas. It is clear that what he witnessed must have been horrible but that, possibly because he was an “official” war artist, not schooled in this particular war, he had no intention of making an anti-war statement. Sargent was a patriot and a believer in the richness of this war against the barbarism of the Germans and how better to convey the inhumanity of the “brutes” as they were depicted by British propaganda than to contrast the behavior of the Hun with the nobility of the English lads outlined against the blank sky. The reception of this painting, both at the time of its first exhibiting and to this day, was and is complex and controversial. Gassed, while admired by the public, has been examined with jaundiced eyes for the past century, an issue examined in Part Two.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.