Walter Richard Sickert (1860-1942)

Part Three

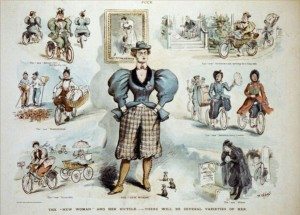

Perhaps because of the interference of the Great War, the term “New Woman” came to become attached to the changing roles of woman after 1918. However, this term had its origins in the fin-de-siècle period as men and women witnessed women taking control of their lives. If men were uneasy about the attempts of women to emancipate themselves from patriarchal control, starting but not ending with gaining the vote, They had only themselves to blame. For nearly a century, since the American Revolution and the French Revolution raised the specter of equal rights, women had been restively waiting to be include and by the end of the nineteenth century signs that women were restive, resentful and rebellions were everywhere. While the Belle Epoch has often been portrayed in Merchant and Ivory tones of romance, real life in England and France was quite different. Women had few legal levers to seek their freedom from male control, but they had a social weapon, refusing to marry. In fact the trend towards not marrying or marrying late was established enough to raise alarm over what was termed, in England, as “Redundant Women,” or women who were not attached to men and who should be shipped out of England to colonies. At least that is the solution proposed by William Rathbone Greg who asked “Why are Women Redundant?” In investigating the “woman’s condition,” he regretfully informed his fellow men, in terms of “we,”

The problem which is so generally though so dimly perceived, and which so many are spasmodically and ambitiously bent on solving, when looked at with a certain degree of completeness,–with an endeavor, that is, to bring together al the scattered phenomena which are usually only seen separately and in detail, appears to resolve itself into this: that there is an enormous and increasing number of single women in the nation, a number quite disproportionate and quite abnormal; a number which positively and relatively, is indicative of an unwholesome social state, and it both productive and prognostic of much wretchedness and wrong. There are hundreds of thousands of women–not to speak more largely still–scattered through all ranks but proportionally must numerous in the middle and upper classes–who has to earn their own living, instead of spending and husbanding the earnings of men; who, not having the narwal duties and labors of wives and mothers, have to carve out artificial and painfully-sought occupations for themselves; who, in place of competing, sweeting, and embellishing the existence of others, are compelled to lead an independent and incomplete existence of their own.

This now-amusing booklet was written in 1869 and by the end of the century, the “problem,” called by Greg a “malady,” and “social evils and errors” was the topic of far more interesting books, written expressly by and for women, who were beginning to write and speak their own discourse. Earning a living on their own, however small their wages, allowed women to be free of a major threat to their lives, health and well being: marriage. A married woman not only gave up legal control over her life and wealth, she also put herself in grave danger, risking her life in childbirth and risked her health when he husband gave her and her children his venereal diseases. By the time laws were passed to rectify these untenable situations–in 1857 women were allowed to divorce under for a few carefully specified reasons, in 1870 and 1887, women gained more control over their own money and in 1891 women were allowed to refuse conjugal relations with their husbands–women had become “New,” wearing trousers, and beyond the control of men.

According to Dr. Andrzej Diniejko,

The term “New Woman” was coined by the writer and public speaker Sarah Grand in 1894 (271). It soon became a popular catch-phrase in newspapers and books. The New Woman, a significant cultural icon of the of the fin de siècle, departed from the stereotypical Victorian woman. She was intelligent, educated, emancipated, independent and self-supporting..The New Woman, a tempting object of ridicule in the press and popular fiction, was generally middle-class, and New Women included social reformers, popular novelists, suffragists, female students and professional women. The contemporary satirical representations of the New Woman usually pictured her riding a bicycle in bloomers and smoking a cigarette.

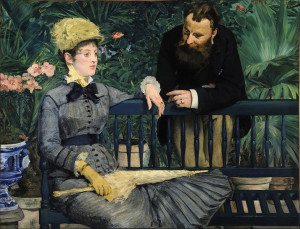

Men in general appear to have not been prepared for this New Woman in their midst, and, mirroring the new literary genre, fin-de-siècle visual culture showed the symptoms of women’s dissatisfaction with married life. During the second half of the nineteenth century, relations between men and women had been difficult for a number of years and the tension between political philosophies that asserted universal rights, regardless of social station or gender, and the refusal to grant these rights to women, can be seen in notable paintings by observant artists. Édouard Manet (1832-1883) showed an upper middle class couple, apparently alienated from one another, in the work In the Observatory (1879). The couple, Jules Guillemot and his wife, known only as “Madame Jules Guillemot,” may have been painted separately in the artist’s studio. They are so isolated and estranged, they appear to be in a state of psychological separation, making communication impossible. Jonathan Crary wrote a chapter on this relatively unknown painting by Manet in his 2001 book, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture, examining the small details. He noted that the “central” element for the painting

..is the woman’s corseted, belted, braceleted, gloved, and be ringed figure. Manet’s painting, like this body (and the coiled, indrawn figure of the man), is powerfully marked by a system of compression and restraint. These indications of bodies reined in coincide with other kinds of subduing and constraint necessary for the construction of an organized and inhibited corporeality.

Édouard Manet. In the Observatory (1879)

There was enough discourse on the rights of women in French culture for women, particularly those of the upper classes, to be increasingly aware of their second class status. They had no legal existence except through the males in their lives. Women and men were so socially segregated and so inherently un-equal that it is difficult to fathom how relationships were either made or maintained. In his book For Moral Ambiguity: National Culture and the Politics of the Family (2001), Michael J. Shapiro remarked upon the analysis of Crary by writing,

The painting works to reconsolidate both a perceptual field being sundered by a breakdown in normative attentiveness and a breakdown in the marriage bond reflected in adulterous relationships.

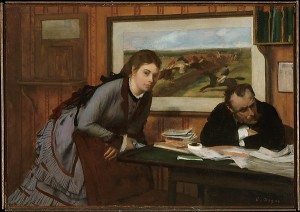

Edgar Degas. Sulking (1870)

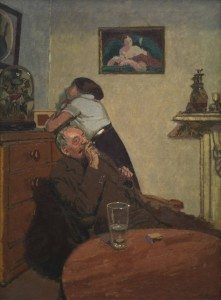

Walter Sickert Ennui (c.1914)

Like Edgar Degas’s Sulking (1870) and like Manet’s painting, In the Conservatory (1879), Walter Sickert’s Ennui (1914), also an ambiguous painting of a bourgeois interior vibrating with tensions between a man and a woman. The domestic scene is carefully painted in a manner that suggested a heightened importance for the artist. It would be too facile to suggest that the tight and controlled style used by all three painters was deployed to impose formal tension as the counterpart to marital relationships under astriction. But the district drawing and level of fini among these artists overlays and binds studies of male female relationships at at time when all orthodox rituals between genders were being reverse engineered. Artists are observers of human nature, and, on the eve of the Great War, Sickert caught two people, an older man and a younger woman, paralyzed by boredom and trapped by conventions that precluded escape. The artist placed the young woman in a corner with her face turned away from the viewer. She seems to be gazing blankly into a clutch of taxidermied birds confined inside a glass globe, called a “bell jar.” The man, who is much older, takes on the role of her keeper, either a father or a husband. Instruments of his control and contentment are close at hand: a carafe of wine on the mantlepiece, a large glass of ale on the table at his elbow. He is smoking a small cigar and has arranged himself in a self-satisfied relaxed posture, raising the question, who is suffering from ennui?

Employing a very Degas-esque device, the table trust like a warning into the viewer’s space, Sickert painted four versions of domestic paralysis and made numerous sketches, studies and prints of an incompatible couple, who are walled off from each other. The blocking table was used by Mary Cassatt in Cup of Tea to prevent the spectator from either joining or rescuing the two nearly comatose tea drinkers, women trapped in bourgeoisie boredom. But Sickert presented something beyond mere boredom in a period predating the kind of mass entertainment that took the place of conversations. The version that was presented to the Tate in 1924 was the most finished and the largest and probably his final word on the topic of marriage. In 2004 Nicola Moorby analyzed this painting of the Tate, noting that

“The physical proximity of the two figures supposes an intimate connection between them such as marriage, but their complete disassociation and lack of engagement with one another creates an atmosphere of isolation, indifference and loneliness. Sickert had previously explored the tensions apparent in the domestic arena in works such as Off to the Pub (c.1912), Sunday Afternoon (c.1912–13) and Jack Ashore (c.1912–13), but none of these portray a situation as explicitly dysfunctional as Ennui.”

Moorby also stressed the artist’s use of the term “ennui,” with the French word conveying a sense of indifference and languor and a sense of nothingness, going far beyond the English term “boredom.” If one takes “ennui” at face value, then the sense that life has no meaning and no purpose could have a dual manifestation: the woman suffers from ennui of her very soul, trapped in a life that is empty because society has denied her a fulfilling role; the man assuages his lack with oral pleasures that dull the pain of ennui.

In its time, Sickert’s large painting, was understood as an interior, theatricializing the former actor’s reenactment of a moment from Balzac or Flaubert–players paralyzed by the hole at the heart of middle class life. But the paralysis, the lack of will to move, the lack of space to change, was also indicative of the Edwardian period. In 1911, it seemed impossible for society to surge forward, to keep up with the technological revolution that was reshaping ordinary life in the new century. No where was the contrast more drastic than the disjuncture between the automobiles chugging down the streets of London and the costumes that dragged women down, clothing that precluded their participation with modern machines–long skirts and huge hats and tight corsets. The Futurists, who would rock the art world to its staid foundations in 1912, expressed this cultural sense of asymmetry–they raged against museums and the past, they were shouting against the ennui of the age: progress was rushing past a population frozen in place, staring into the bell jar.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.